We need to be aware of the pitfalls of our unconscious biases if we are to become the self-aware leaders we want to be.

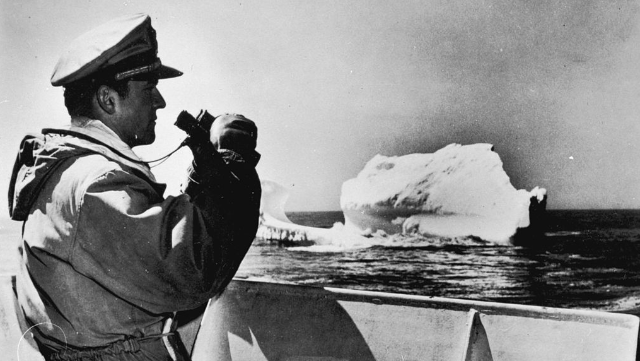

Consider, if you will, the iceberg.

Huge blocks of freshwater ice that float freely in the open seas; harbingers of a warming planet; nemesis of RMS Titanic and, for the psychologist Sigmund Freud, a metaphor for how the human mind works.

For Freud, while our conscious thoughts and feelings bob along happily above the surface, what really makes us tick, the most important part of the mind that drives most of our behaviours, remains underwater, hidden from view, weighed down by our own murky waters of repression and denial.

Welcome to the idea of the unconscious, that enormous block of submerged ice that might not be visible to us, but still exerts an influence over how we behave. Enough of the metaphor, perhaps, but it’s a graphic way to consider a theory of personality that, despite its detractors, still offers insight into why it can be so hard to know ourselves, especially when it comes to those blind spots and hidden biases we all have and that threaten to get in the way of the plain sailing we’d all like to achieve at work and beyond.

The concept of the unconscious is not original to Freud. The idea had been doing the rounds in philosophical circles for a while, with the term coined by German philosopher Friedrich Schelling in the 18th century, and apparently translated into English by none other than romantic poet and idealist Samuel Taylor Coleridge (opium-induced journeys into the unconscious imagination, anyone?). But it’s with Freud that the idea reaches its apogee.

Freud’s iceberg has three levels. Above the waterline, our conscious mind consists of all the mental processes of which we are immediately aware. Just below the waterline, Freud’s preconscious contains thoughts and feelings that we may not currently be aware of, but which can easily be brought to consciousness, a sort of mental waiting room in which thoughts remain until they “succeed in attracting the eye of the conscious”. And, below the preconscious lies the unconscious mind, those mental processes that are inaccessible to consciousness but still influence our judgements, feelings and behaviours.

It’s this unconscious, according to Freud, that is the primary source of human behaviour. As RMS Titanic found out, the most important part of the iceberg is the bit we cannot (or prefer not to) see. But try as we might to hide or repress experiences or impulses that might be unpalatable to our rational, conscious selves, they have a habit of escaping.

That may be through dreams, jokes, Freud’s parapraxis or what have come to be known as Freudian slips, when we mean to say, write or remember one thing but instead say, write or remember something entirely different. Or as the old joke goes, a Freudian slip is when you say one thing but mean a mother.

Such slips might indicate something we actually want to express but feel unable to, or represent unrealised feeling that haven’t yet become conscious. Freud might have an interesting interpretation for the time we incorrectly ascribed to Dave from Accounts that now-infamous incident at the staff party.

The bottom line is that Freudian theory is based on the idea that the unconscious mind governs our behaviour to a much greater extent than we might think. For Freud, the goal of psychoanalysis is to identify and shift those hidden unconscious motives into the light of consciousness so that we can understand better what’s driving us. And with that insight comes, to some degree, the ability to control and manage what we think and do and how we behave.

A tendency towards bias

So far, so good. But whether or not we agree with Freud or subscribe to his remedy, the problem is that being able to identify and manage those unconscious thoughts and feelings takes a whole lot of mental effort.

As Daniel Kahneman’s work has so eloquently shown us, our speedier, more intuitive System 1 thinking tends to prevail as a way of protecting us from the cognitive strain of slower, more deliberate System 2 thinking. And the cost of these cognitive shortcuts? A tendency towards cognitive or unconscious bias, to follow and act on our first impressions or impulses, often despite evidence to the contrary.

There are more cognitive biases than even the best psychologist could readily name. We all have them. They influence our understanding, actions and decisions, but, because we are often not aware of them, they can manifest themselves in subtle, insidious ways. We might pay too much attention to our first instincts without properly weighing up the pros and cons; we might naturally gravitate towards hiring someone because they have a similar background, interests or experience; we might make unwarranted assumptions about certain individuals (sorry, Dave), groups or even ourselves.

In the workplace, where we have to make daily judgements about tasks and relationships, it’s easy to see how these biases might get in the way, no matter how well intentioned we want to be. We might think we’re entirely rational, objective and logical, but we can’t entirely escape our unconscious or implicit attitudes and assumptions.

At best, we can merely acknowledge and try to mitigate them. That’s why building self-awareness can help, even if, as we’ll see below, awareness itself is not always a complete solution. Undetected or untested, they can trip us up, contribute to poor decision-making and bad judgements, even lead to stereotyping and discrimination.

In the worst-case scenario, our tendency towards groupthink reinforces those biases and embeds them at an organisational, as well as an individual, level. We need only remember the damning judgement that London’s Metropolitan Police Force had shown itself to be “institutionally racist” when unsuccessfully investigating the murder of black teenager Stephen Lawrence.

Stanford psychologist Jennifer Eberhardt tells a similar story to illustrate the extent to which bias against black men has become so unconsciously and insidiously embedded in American society that even her five-year-old son expressed the hope that their plane would not be “robbed” by the only other black passenger.

Such cultural stereotyping has also been researched and tested by Princeton’s Sarah-Jane Leslie. Intrigued as to why academic disciplines often associated with “unteachable brilliance”, such as philosophy or physics, tend to be populated by fewer women, Leslie wanted to test how early these stereotypes tend to manifest themselves. She found that, even by the age of six, girls were much less likely to identify a super-smart character in a gender-neutral story as being female.

Evidence, if any were needed, that such bias can be deep-rooted and, perhaps unsurprisingly, hard to address and counter.

Tackling unconscious bias: the limits of unconscious bias training

Awareness of unconscious or implicit bias at work has grown hugely in recent years as we look to tackle the bias that can lead to discrimination and exclusion in organisations of all types and sizes. We know that matters. More than ever, we have the evidence that diverse and inclusive workforces are not just a positive thing in their own right, but an important driver for organisational reputation and growth.

Management consulting firm McKinsey has been tracking the impact of more diverse boards on organisational success for almost a decade. Its latest report shows that more gender-diverse boards can improve performance by 25%, while, for ethnically diverse boards, that figure rises to 36%. Nor is diversity just about key demographics, important as that is. Widening the talent pool to include cognitive diversity – differences in how people think, process information and relate to the world – is also a proven route to better performance and more of that crucial creativity and innovation.

That doesn’t mean that all is well in the world of diversity, equality and inclusion. Greater awareness of bias – conscious or unconscious – has not made those biases go away. The imbalanced gender challenges of working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic or the ongoing movement for racial justice in the wake of the murder of George Floyd show us that creating more inclusive workplaces is not for the faint-hearted, even as the imperative to ‘do something’ in this space has become more compelling.

Enter a diversity training industry that is worth $8bn a year in the US alone. And much of this training is aimed squarely at tackling the role unconscious bias can play in fuelling discrimination. Implicit or unconscious bias training (UBT) is designed to do three things: make people aware of their biases, often using a diagnostic such as the Implicit Association Test (IAT); provide tools and techniques to adjust automatic ways of thinking and, as result, modify behaviour to reduce bias.

It sounds plausible – after all, it seems logical that increasing self-awareness around our biases can be an important step towards tackling them. But placing the burden of fostering diversity and inclusion at work on the slim shoulders of UBT might, at best, be ambitious.

Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic is just one of a number of academics and thinkers who are sceptical about its effectiveness. Increasing awareness around bias is not without its challenges. In the worst cases, mandated or badly delivered training can backfire, actively reinforcing stereotypes by making people feel that, because bias is universal, it’s somehow inevitable or provoking a backlash from people who feel defensive about being seen as sexist or racist.

For minority group members, raising awareness of difference can also increase feelings of alienation. At best, it’s likely to be preaching to the converted; research has shown that prejudice reduction programmes are much more effective when people are already open-minded, altruistic and concerned about their prejudices to begin with.

For Chamorro-Premuzic, that’s because the main problem with stereotypes is not that people are – in general – unaware of them, but that they agree with them, even if they might not like to admit it. In other words, most people have conscious biases.

Back in 2018, coffee giant Starbucks made the headlines when it closed 8,000 of its shops across the US to conduct implicit bias training after the unfortunate (and completely unjustified) arrest of two black men at one of its branches. Debates around the effectiveness of these bias training sessions went mainstream.

The company was praised by some for taking racism seriously; but the move was condemned by others as anything from an ill-conceived management box-ticking exercise to a straight publicity stunt. Perhaps the real issue was that UBT is simply not designed to tackle the conscious bias that was the main culprit in the event in Philadelphia in the first place.

Even if we believe that unconscious bias does play a role in stereotyping, questions have also been raised about the main tool used to measure it. The fact that the IAT has been around for years doesn’t mean that it’s without controversy.

The test measures people’s reaction time in response to different combinations of words or photographs (female or male, black or white, smart or stupid) to assess whether people are quicker to associate positives or negatives with a particular demographic category. But, like other personality tests, it scores poorly on the issue of replicability: someone taking the test on a Monday might well receive a very different set of results if they were to retake the test on the following Wednesday.

An even bigger problem is that there’s a weak correlation between IAT scores that supposedly reflect our unconscious biases and our actual behaviours. In other words, just because an IAT result suggests that we might be sexist, it doesn’t mean that we will act in a sexist way – or vice versa. IAT data is not an effective predictor of future behaviour.

Chamorro-Premuzic also reminds us that, even at the best of times, we humans are often pretty poor at acting in accordance with our beliefs. So, if we want to improve the effectiveness of diversity and inclusion interventions, simply making our unconscious thoughts and beliefs more conscious is of limited value when it comes to what actually happens as a result.

Defenders of UBT will point to the fact that that’s not really the point: it’s not intended as a silver bullet. Rather, its use is based on the not-unreasonable assumption that it’s important to recognise and address unconscious attitudes and stereotypes. And, if carefully deployed, it can be useful for awareness raising. But even its staunchest supporters realise that, on its own, and in isolation, its ability to change behaviours – the real drivers of change – is limited.

Increasingly, too, UBT’s focus on individual bias feels at odds with the understanding that change needs long-term organisation-wide cultural change, with buy-in at the highest levels, driven by everything from organisational structures, policies and procedures to tone, language and behaviours. And, for that to happen, organisations need to experiment with and deploy a whole range of strategies, techniques and tools, of which UBT might be just one.

Sociologists Frank Dobbin and Alexandra Kalev rehearse a number of arguments against mandated, command-and-control-led diversity initiatives, including UBT. They also look at some practical strategies for inclusion which don’t focus on control, but instead apply three basic principles:

1. Engage managers in solving the problem

When managers actively help boost diversity in their companies, they begin to think of themselves as diversity champions. Unsurprisingly, asking for volunteers to lead positive programmes for change (‘help us find a greater variety of promising employees’) works better than “blaming and shaming them with rules and re-education”. Mentoring programmes are also positive, not only for the mentees from under-represented groups, but as a tool for breaking down bias among the mentors.

2. Expose them to people from different groups

More contact between groups can lessen bias. One example of this is the idea of immersive experience, which gives participants the opportunity to spend stereotype-busting time with particular groups, the better to understand their needs and the barriers they might face at work.

An Ashridge-Barclays initiative to create and evaluate an immersive CSR activity as an alternative to diversity training shows how powerful it can be. It brought together 39 able-bodied Barclays executives with an equal number of people with disabilities to sail one of the Jubilee Sailing Trust’s accessible tall ships as working crew.

Measures of implicit and explicit attitudes taken before and after the voyage showed a significant shift in attitudes among the able-bodied executives. Immersion had made them less likely to view their crew mates’ disabilities as their defining characteristic.

3. Encourage social accountability for change

People generally want to be seen to be doing the right thing. Improving transparency to highlight discrepancies (as with gender or ethnicity pay reporting), creating diversity taskforces and having a nominated diversity manager tends to make people consider and amend behaviours more readily.

Tackling unconscious bias: strategies for 'debiasing'

The problems with UBT does not mean that increasing our self-awareness around our unconscious biases is a wholly empty exercise. We might not be able to rely on UBT to solve ongoing diversity, equality and inclusion conundrums, but that’s not to say that making more of the unconscious conscious is without value.

Nor are our unconscious biases solely related to how we might unconsciously feel about others who may be different to us. As we’ve seen, cognitive bias is simply a part of the human condition, manifesting itself in a variety of ways.

We may bloody-mindedly press on with a project that’s going nowhere because we’re damned if we’re going to stop after all the time and effort we’ve already invested (sunk cost fallacy). We might be much more likely to accept the word of someone in authority (authority bias). We might take the plaudits if that presentation went well, but point the finger at the room layout, the audience, the lighting, anything except ourselves if it goes less well (self-serving bias).

Acknowledging and mitigating these biases, then, is about how we think and behave in our everyday lives. And it’s that awareness that gives us a jumping-off point for taking action to minimise the impact bias can have on everything from decision-making to building positive relationships at work.

Writing in Harvard Business Review, Jack B. Soll, Katherine L. Milkman and John W. Payne reiterate that the first step in tackling any cognitive bias is to acknowledge that we all have them, and that we’re likely to be especially prone to relying on often dubious intuition and impulses when we’re under stress or feeling overwhelmed. But they argue that awareness alone isn’t enough; we also need strategies for overcoming them.

Soll et al use the lovely phrase “cognitive misers” to explain why we so often default to Kahneman’s System 1 thinking: we don’t like to spend our mental energy entertaining uncertainty; it’s much easier to seek closure, even if that means narrowing options and making premature or ill-considered judgements. They argue that, to “debias” our judgements and decisions, we need to broaden our perspective on three fronts:

Thinking about the future

We need to consider a wider range of outcomes for what we say and do. Experiment with scenarios; take a time out and think twice. If we think we might be biased when making a hiring decision, seek some outside perspective as a check and balance; spending time with others who have a different worldview is a sure-fire way of tackling our in-built prejudices. If we have a tendency to catastrophise, always thinking the worst will happen, identifying and exploring a range of possible outcomes will help us to gain some perspective.

We might also make use of the pre-mortem technique to imagine future failure and track back to that failure’s causes or thinking that threatens to derail us.

Thinking about objectives

We also need to have “an expansive mindset” when it comes to what we’re looking to achieve. That means being open to a range of perspectives and ideas from a range of different people: the right goal might not always be the first that comes to mind.

Thinking about options

We probably have more options available to us at any one time than we may think. In our rush to closure, it’s easy to go for a simple yes/no framing, but we need to avoid this “cognitive rigidity” which takes us away from exploring a greater range of possibilities. Asking the simple question what else could I do? is a useful trick for reopening the options we really do have.

This idea that we need to be more expansive, to get more comfortable with the unknown, to be curious and open to other perspectives speaks to the heart of tackling unconscious bias. Daniel Kahneman neatly sums up our tendency towards the opposite, the status quo, when he wrote: “Our comforting conviction that the world makes sense rests on a secure foundation: our almost unlimited ability to ignore our ignorance.”

If Freud’s iceberg teaches us anything, it is that we ignore that ignorance at our peril. We’re all complex beings with a whole host of thoughts, experiences and impulses, many of which lurk beneath the waters of consciousness, but can still derail us when we need to make those critical judgements and decisions at work.

While we might not opt for a full course of psychotherapy in an effort to bring the repressed unconscious to light, we can improve our awareness of how our unconscious selves can manifest in biases that get in the way of how we want to be perceived and what we want to achieve. By doing that, we give ourselves the tools we need to question our first impulses and start to tackle our biases in more open and inclusive ways.

What’s your default mode for making judgements and decisions? Are you being tricked by intuition?

How might your biases affect how you view under-represented groups?

Test your understanding

-

Describe Freud’s iceberg metaphor for how the human mind works.

-

Outline the difference between Kahneman’s System 1 and System 2 thinking.

-

Identify three limitations of unconscious bias training.

What does it mean for you?

-

Reflect on how your own biases might be impacting on your performance at work.

-

Identify two biases you have and make a plan for how you might manage or mitigate them.