Simple problem-defining techniques can help us to focus on the right issue before we start looking for solutions, saving time and missteps down the line.

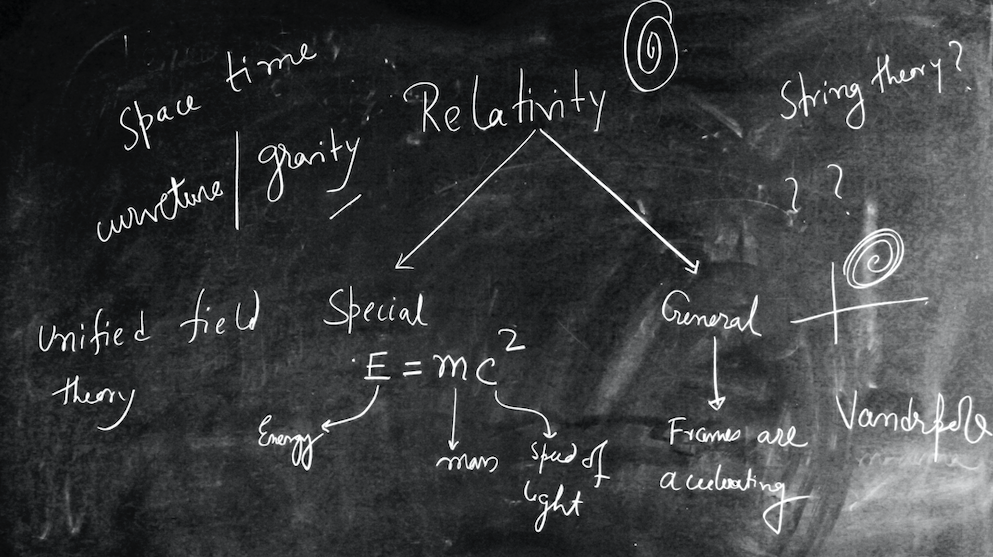

“If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and five minutes thinking about the solution,” said Albert Einstein – neatly summarising a key stage of any problem-solving process.

It’s all too easy, when faced with a challenge – especially if under pressure – to skip over the problem itself and push on to possible solutions. But for anything other than the simplest of decisions, investing the time to research, articulate and clarify what’s at stake can save much wasted effort later on.

This doesn’t mean that we should get stuck in a loop of endless navel-gazing or that we’re always looking for perfection. Nor should we cerebrate in a crisis, where action must come first and we turn to thinking as the situation moves from chaos to complexity.

But where the situation allows, we should put aside time to get to the heart of the issue – with the help of some root cause analysis (RCA).

Finding the root cause

RCA – as its name suggests – is a systematic process for identifying ‘root causes’ of problems or issues and coming up with a plan for responding to them. It’s designed to be comprehensive, holistic and preventive, revealing key relationships among variables.

Rather than focusing on the symptoms of a problem, we seek out and remedy its root causes, while also addressing the symptoms to achieve short-term relief.

This means scrutinising why and how something has happened (or is happening), rather than concentrating on who is to blame, and doing so in a methodical way – gathering cause-effect evidence to support our theories. We then devise a corrective course of action and consider how to prevent the problem occurring in future.

There are various ways in which we can conduct RCA, but all revolve around harnessing our curiosity to explore issues fully, defining a problem statement and breaking down the issue into smaller elements in order to get to the crux of it.

The ‘5 Whys’

With this simple approach (which can also be used as part of the other RCA techniques below) we channel our inner toddler by asking “why?” something is happening, and following up every answer with a further “why?” question, so that we dig deeper and deeper into the issue.

Generally, five ‘why questions’ get to the root cause of the problem – but this may be achieved with fewer (or substantially more) depending on its complexity.

The aim is to avoid making assumptions and to consider the issue objectively and methodically.

For example:

The root cause of the problem is therefore the lack of a process for calendar management to ensure that time off doesn’t clash – so this is something we can action to prevent it happening in future. The process has prevented us from jumping to the conclusions about the behaviour of members of the sales team and enabled us to come up with a simple and practical solution.

Socratic Questioning

The ‘5 Whys’ can be incorporated into Socratic Questioning, which enables critical analysis of an issue or problem via structured logic. According to ancient Greek philosopher Socrates: “The disciplined practice of thoughtful questioning enables the scholar/student to examine ideas and be able to determine the validity of those ideas.”

Six types of question are employed to do this:

Questions that clarify

For example:

- What do you mean by…?

- Can you provide an example?

- Could you explain further?

- Are you saying that…?

Questions that challenge assumptions

For example:

- Are you assuming that...?

- Is that always the case?

- How could we prove/disprove that belief?

- What would happen if…?

Questions that challenge reason and evidence

For example:

- Why do you think this is?

- What evidence supports that?

- Can you give me an example?

- Why do you say that?

Questions that consider alternative perspectives

For example:

- Are there alternative viewpoints?

- What makes your perspective more valid?

- Where might your biases lie?

- Are there any alternatives?

Questions that consider implications and consequences

For example:

- What if you’re wrong?

- How does that affect…?

- What are the long-term implications of this?

- What will happen if we don’t change?

Questions about questions

For example:

- What is the point of this question?

- What do you think was important about that question?

- Why do you think I asked this question?

- What question might it have been better to ask?

Questioning our evidence and assumptions – and even the questions we are using to do so – enables us to move past and dismantle pre-existing ideas and to look again at the elements we think we already understand. The ultimate aim is to increase understanding by enquiry – whether we’re brainstorming with others or playing devil’s advocate with ourselves.

The Drill Down technique and Fishbone Analysis

To break down complex problems into progressively smaller parts, we may decide to use the Drill Down technique, creating a series of columns from left to right on a large piece of paper (or digitally, if preferred).

In our left-most column, we write our problem statement (or effect). The factors causing this problem are then added to the second column and the factors causing these problems are detailed in the third column. We therefore keep 'drilling down' until the true causes of the problem are identified.

An even more visual way of considering cause and effect (often used in project management) is offered by Fishbone Analysis – so called because it creates a causal diagram that resembles a fish. (This is also known as an Ishikawa diagram – or Fishikawa! – after the Japanese organisational theorist Kaoru Ishikawa who invented it).

To work through Fishbone Analysis:

- First, we come up with our problem statement, writing it at the end of a long arrow – at the mouth of the fish (see example above).

- Next, we identify the major ‘cause categories’ for our problem – which will vary according to the issue at hand. With our previous example of losing a client due to the tardiness of sales team, we may define the categories as: People, Processes, Resources, Technology, Management, Change. We should write these as branches from the main arrow.

- We then brainstorm all possible causes of the problem, asking why it happens and writing each reason as a branch from the relevant category.

- We add sub-causes which branch off from the various branch causes – this is where our ‘5 whys’ technique can come into play.

To find the root causes of the problem, we work backwards and flesh out the fish’s bones. This helps us to visualise our situation and to get to the heart of the issue before we start thinking about potential solutions.

Tackling recurring problems

RCA can be applied to a range of different problems, across any type of industry, helping us to trace problems to their origins rather than simply addressing the symptoms they cause.

It is not infallible and can be undermined by a number of factors, from a vague problem statement to a reliance on guesses or assumptions. However, by fixing the underlying systems and processes, we can often break the cycle of ‘incident firefighting’ – whereby we are continually dealing with crisis situations caused by recurring problems – getting rid of issues for good.

Our investment of time will be repaid many times over if we are able to pinpoint and define genuine problems at the earliest possible stage rather than jumping immediately into flawed solution finding – and trying to fix all the wrong things. It’s the most important part of problem-solving and, as Einstein understood, it’s integral to making the best possible decisions in business and beyond.

Test your understanding

-

Explain why it’s important to define a problem clearly before embarking on solution finding or decision-making.

-

Describe what root cause analysis (RCA) involves and highlight one of the key techniques we can use.

What does it mean for you?

-

Try out one or more of the RCA techniques when working through a complex problem to help identify the crux of the issue.