Getting to grips with budgeting can help us to head off in the right direction – and stay on course.

Budgeting (aka financial planning) might not sound like a thrilling activity. But when we do it well, our budget can become a roadmap to the place we want to go in the future and a way of embodying our values.

In the most basic of terms, a budget or financial plan is a way of deciding how to divide our financial resources across different activities or projects, all of which have costs. A budget plots a variety of costs (people, materials, overheads) against a range of income streams, assessing what’s affordable and helping us to prioritise investment – with an eye to profitability as well as just top-line income.

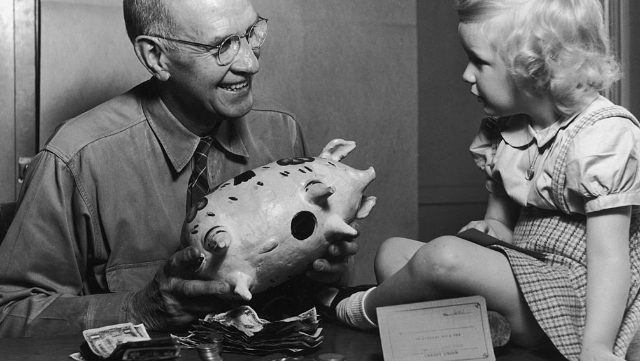

Most of us have been doing this informally for years, ever since we received our first pocket money and started working out exactly how many Flying Saucers, Gobstoppers and Drumstick lollies we could buy for 50p – and what we needed to forgo to save for the occasional Sherbet Fountain.

Now as leaders, we need to work with our teams to make the very best use of our resources. And this means getting to grips with budgeting.

Broadly, this involves:

- estimating income and expenses over a defined period.

- allocating resources strategically and appropriately in each area in order to achieve our objectives (i.e. making a financial plan).

- managing day-to-day team activities in line with the allocated budget.

Think of it as actively telling your money where to go instead of passively wondering where the heck it went.

Add this into the benefits column

While our finance departments are often a significant help, they cannot manage our budgets for us.

Their focus is ensuring that the budgets of every department fit together coherently in line with the overall financial goals of our organisation. It’s up to us to take confident ownership of the costs and budgets in our own area.

Far from being a burden, this can help us to do our own jobs better, by – over time – allowing us to build up our intuitive understanding of finance, and how the budgeting process can help us to reinforce our values and deliver on strategic and operational plans.

While we’ll need to take the lead, we should also make every effort to involve and listen to those around us when creating, implementing and monitoring our budgets. With more than one perspective, we are less likely to make unhelpful assumptions or to change things without sound justification. Involving others will also improve buy-in and create a sense that everyone can contribute to sound financial planning and management.

Specific benefits of budgeting include:

Helping us to communicate our priorities and align effort with goals

Whatever we might say, it’s our budgets that walk the walk on our values, so they must be in step with our goals and objectives. Former US president Barack Obama posits that a budget is "an embodiment of our values". And Joe Biden agrees, adding "don’t tell me what you value, show me your budget, and I’ll tell you what you value".

Acting as a real-time feedback tool and early warning system

The deliverables in our budget can serve as key milestones, helping us manage people’s time and deliver feedback on their contributions. Through careful monitoring, we can spot early signs of things going awry and make any necessary adjustments, whether that’s an overspend in marketing expenditure or a significant market shift. Benjamin Franklin reminds us, "a small leak will sink a great ship"; managing and monitoring budgets helps us to see and act on both minor and emerging problems.

Approaches to budgeting

Before we start the process of creating a budget, it’s useful to think what our approach is going to be. As a starting point, the previous year’s budget offers a useful reference, reminding us of the categories and amounts of income or expenditure that were previously included. However, how we choose to use that baseline will vary depending on the context we’re working in and our budgeting goal.

Zero-based budgeting (ZBB) - a ‘start afresh’ approach

With zero base budgeting, the premise is that, for each new budget period, the budget categories all start with no money (zero) allocated to them. Each item is revisited to assess whether it should remain or be removed. New categories might also be added if our business has changed. The remaining and new budget items then have funds allocated to them in line with the needs determined by our current strategy.

The advantage of ZBB is that each budget item is justified in the context of future plans rather than past performance. However, it can be time-consuming, and is not always necessary.

Incremental budgeting – a ‘business as usual’ approach

With incremental budgeting, existing items are allocated a percentage more (or less) than the previous budget, taking into account adjustments for things such as proposed salary rises, inflation or changes in business activity.

This type of budget works well when overall strategy and objectives have not changed significantly since the previous budgetary period.

The advantage of incremental budgeting is that it is relatively quick and simple to look at the historic data and make small adjustments to allocate resources. It only works, however, if the historic budget data we’re using is accurate. We also need to be sure that we are fully taking into account any changes to strategy, goals and how we operate. It can be all too easy, for example, to keep on budgeting for a line of expenditure that we can probably live without.

A hybrid approach – combining the benefits of both

Often, the two approaches can work well in tandem. It may be a good idea to adopt a zero-based approach every five years or so (or more frequently if we work in a fast-paced sector) with incremental budgets in the intervening period.

We might also use zero-based reviews of any specific activities or areas that are undergoing significant change (for example, a production team investing in new technology) while still using incremental budgets for other areas of expenditure – or for other teams by way of comparison.

In deciding which approach is right for us, it may help to ask:

- Have my team’s activities changed much from the previous budget period?

- What are our objectives and the organisation’s strategy for the period ahead?

- How accurate is the data in the previous budget?

- Were there major budget variances (see below) last time?

A typical budgeting cycle

A budget (or accounting) period is typically one year divided into 12 months for reporting and review, but this is not always the case. For example, specific events or projects such as a new product or service might have their own budget schedule that might sit within the usual accounting period, or across several.

But whether we are budgeting for our day-to-day activities or a specific project, we are likely to go through five core stages:

Stage 1: Establish goal

First, we need to determine what the budget is for, that is, what we are trying to achieve.

All decisions should be framed within the wider goals and objectives of our organisation, and our team’s role in advancing that mission. However, we must be specific about the deliverables we need to achieve with our budget, and the resources we’ll require to produce the desired results.

These considerations need to be informed by an understanding of our industry and marketplace, current trends, likely inflation, worldwide and domestic political events (for example, those that might affect exchange rates), and any other relevant factors that could impact on revenue streams and costs.

Stage 2: Decide on type/s

There is rarely, if ever, a single budget for an organisation to control its finances. Rather, there are several types of budget – often used in combination – and the content and format needed will depend on our established goal:

Sales (income) budgets: the quantity of product or service we intend to sell or deliver over a given budget period.

This will include details of the sales we make (split by cash and credit sales) and a breakdown of the costs directly related to making those sales; for example, the cost of production, packaging or our sales team’s travel expenses.

Project budgets: how much money we are going to spend on the resources involved in our particular project.

These are likely to set out individual costs such as labour, materials and equipment.

Departmental/team cost budgets: how much needs to be spent (within a set period) for our department/team to carry out its day-to-day functions and achieve its objectives.

This may include team payroll costs, training and development, materials and equipment, overheads and general administrative costs.

Production budgets: the volume of products/services that will be produced/delivered in a given time period and how much this will cost.

Capital expenditure budgets: how much we will need to spend on capital items (large items of equipment, such as computer equipment or furniture) for our team.

These large items are likely to be expensive, so this type of budget enables us to think about any new items or replacements that may be required and how long they might last, and to spread the cost over more than one year.

Cash budgets: the likely cash flow (actual cash needed to cover outgoings) for the period ahead, enabling us to plan activities around that profile.

Profit and loss budgets: how much profit we will make given a certain level of revenue and expenditure.

They can be created at organisation, team or product level, and combine income and cost budgets to give us a sense of whether our predicted sales will cover our predicted expenditure.

Stock budgets: help us plan how much stock we should have on the premises at any one time according to our predicted customer demand and speed of production.

‘Stock’ comprises raw materials, work-in-progress and finished goods – things that will eventually go into the product we are selling to our customers.

Credit control budgets: allow the cash that is coming in from customers to be tracked against the credit period they have been given

The budget type will always impact on the extent of our involvement.

Sometimes a finance team will lead on cash flow forecasting, for example, although they’ll need our input on the budget details to construct it.

The amount of information we need, who we must speak to in order to gather it, and how long the whole process is likely to take will also vary. We therefore need to be mindful of other people’s work commitments and realistic about when they are likely to report back to us.

The frequency of finance department reviews and reports – such as monthly management accounts and annual financial statements – is also a factor. We need to be aware of related deadlines and procedures in order to manage our time effectively.

Stage 3: Plan and allocate

Armed with this information, we then need to understand how sales/income and cost budgets will be generated.

When estimating and allocating costs, we should think about different types of costs, which include:

Fixed costs: will not vary with the level of work or production that is taking place during a given period of time. They include things like premises costs and insurance.

Variable costs: these – as their name suggests – do vary in direct proportion to the activity being undertaken; for example, the materials or energy we consume as part of our work.

We should also be aware of semi-variable costs, like direct production or marketing costs, that may be influenced by a range of factors, like changes in sales volumes.

Total cost = total fixed costs + total variable (and semi-variable) costs: knowing this information allows us to work out the price we need to charge and the volume we need to sell in order to break even (i.e. the point in any business venture when the income is equal to the costs), to make a profit, or to make an informed investment decision for a new product or project.

In many cases, we will need to use estimated figures for certain costs. So, as well as drawing on our own experience, we should make use of previous accounts, similar projects, and current research and data to help us make our estimations as sound as possible.

We should also be mindful of two other types of costs that won’t have their own budget line, but may shape our approach to the costs we do need to expend, and why.

Sunk costs: costs that have already been incurred.

While these should be irrelevant to the decision-making process, we often feel a very human need (known as sunk cost fallacy) to demonstrate that a previous cost has been worthwhile.

For example, if three months ago, we invested £100,000 in a new software package to improve productivity, we’d naturally feel concerned if a totally new – and much better – product were to be released a few months later. In such as case, we should consider the original £100,000 as a sunk cost. The decision to invest should be made solely on the expected payback of the new software package.

Opportunity costs: these represent the potential benefits our organisation misses out on when we choose one option over an alternative.

For example, if we decided to spend all of our time and resources on product A, then we’re not going to be able to take full advantage of product B or C. So our costs are not just related to the costs associated with project A, but also with the potential upside project B or C might offer.

Understanding these potential missed opportunities encourages better decision-making.

Stage 4: Implement and monitor

Once we have created our budget, we need to implement it – and then monitor our performance against it.

Every organisation has its own ways of assessing whether targets are being met. These might include comparing results against Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), looking at productivity records to evaluate progress and output, analysing sales patterns or conducting internal and external audits.

Monitoring budgets should always be a priority. We might, for example, have a standing item at the top of an appropriate team meeting agenda, or hold separate, regular budget monitoring sessions. We might also set time aside with individual team members to keep on top of progress on any income and expenditure they’re responsible for.

We need to be alert to any warning signs that things might be going off track. This might be a sign that our budget assumptions might have been wrong. Or perhaps our implementation is off, with a mismatch between our budgets and operational plans. And even if we’ve planned rigorously and carefully, we can always be blown off course by unforeseen circumstances. That’s why it always makes sense to include a small contingency fund in any budget, especially for activity that’s emerging or more uncertain.

Another important aspect of budget monitoring is to share details of the progress we’re making. As we’ve seen, we’re likely to have to contribute to formal financial reports, such as monthly management accounts. But sharing financial information (where we can) with our teams is also important. Good news is always motivating. And even when the picture is less rosy, it’s important for our colleagues to know the true picture. Sharing the details may result in useful suggestions for mitigating actions, such as improving sales or reducing expenditure.

Stage 5: Evaluate the process

While some organisations skip this part of the process, taking time to reflect on how effective the budgeting cycle has been can help to improve the accuracy of our budgets in future.

Reviews should be prompt and thorough, with all of the relevant people meeting soon after the end of the budget period. When we’re taking part in a review meeting, we need to be prepared, reviewing performance against budget and asking ourselves some key questions. For example:

- Did our budget help us to achieve our goal?

- Was it realistic?

- Did the data lead us to make any incorrect assumptions?

- What went well?

- What went less well – and are there any mitigating factors?

- What should we do differently next time?

- What new ideas could help with our next budget?

Once we’ve conducted a thorough review, it’s important to list the key lessons learnt and translate them into agreed action points, confirming who will take responsibility for implementing each action. And, of course, we should use what we’ve learnt when drafting our next budget.

What to do when things don’t add up

A budget variance is the difference between the budgeted amount of income or expenditure and the actual sales we’re making or the costs we’re incurring. Variances can be positive or negative, and the factors may be caused by internal (our priorities may have changed, or we may have lost a key member of staff) or external (a new competitor taking market share, perhaps, or disruption to a supply chain).

Either way, we need to take appropriate action. Here are some questions we might ask ourselves:

Is the data correct?

Might the variance be due to a systems glitch rather than a problem with the real figures?

We should always double-check our own calculations, especially when working under pressure. While we wouldn’t have had Popeye if the iron content of spinach hadn't been miscalculated by a German chemist who misplaced a decimal point, the French would also not have had 1,860 SNCF trains too that were too ‘fat’ for their platforms, an expensive error which caused the operator to start quietly ‘shaving’ the edges of affected platforms while swallowing costs of at least €50 million ($68.4m).

The stakes might not be quite so high for our own departmental expenditure, but we get the point.

Is our own financial ‘housekeeping’ up to scratch?

We need to get our own houses in order. For example, are we checking invoices properly to ensure that expenditure is correctly authorised and allocated? Are all purchase orders correctly authorised by a named individual with purchasing authority? And have we invoiced for all the things we’ve sold or work that we’ve done or applied for any funding available to us?

All expenses and allowances should also be properly authorised. Keep a close eye on items including overtime and travel expenses, and encourage people to make the claims they need on time and accurately.

Are we getting value for money from our suppliers?

Keeping the terms of business with our suppliers under review will help to keep our budgets on track. If our existing suppliers have put their prices up, or if the level of service is not up to scratch, it might be necessary to change supplier. It’s also wise to have a ‘commitments’ system, whereby everyone in the team takes into account existing commitments before ordering goods and services from new suppliers. Expense codes can be helpful for monitoring when we have reached the full budget allocation for a specific purchase type.

Do we understand the true cost of employing people?

People costs are often the single biggest cost for an organisation. We need to take care when building staffing requirements into our budgets, and have a clear business case for changes throughout the budget period.

These costs are not just about the salary we pay. We also need to take into account on-costs, such as any employer pension contributions, staff-related expenses (for example travel costs) and, in the UK, tax requirements (like National Insurance and PAYE). It’s been estimated that the true cost of an employee could be as much as 1.7 times their basic salary.

Do we have a timing (phasing) issue?

When we budget, we need to make our best estimate for when our income will come in and our costs expended. Business is often seasonal, so simply dividing the total income or expense by 12 months won’t always help us to monitor progress effectively. For example, in many countries, a retail or hospitality business might expect a particularly strong sales performance in the run-up to Christmas or other festivals. Or we may have to pay for raw materials for a new product at a certain time of the year.

If we are not alert to these kinds of timing issues, it’s likely that we’ll have budget variances that could have been avoided – and that will probably even out as the budget year progresses. It can make it hard, though, to understand whether those variances are solely down to timing, or represent an underlying trend we should be aware of.

If the variance is small and unlikely to impact on our overall budget, going through the above checklist may be sufficient. However, it’s worth checking in with finance colleagues to see what controls they have around variance amounts, and what scale of variance is acceptable. We may need to review our priorities, cut back on some of our activities and adjust the distribution of funds in our budget.

If our assumptions or circumstances have changed drastically since creating our budget, we might need a complete reforecast, creating a separate, revised budget that uses year-to-date results as well as our best estimate for the remaining months of the budget period.

Avoiding crossed vires

As the world is unpredictable, choosing to transfer funds from one area of the budget to another – known as virement – can be a useful option. However, we still need to know what authorisation is required and any restrictions that apply. For example, for large virement levels, there are likely to be stipulations, such as the overspend being a necessary item that could not reasonably have been anticipated (health and safety equipment, for example).

Similarly, we should always check to see whether any funds that have not yet been called upon can be carried forward to the next budget period. A ‘use it or lose it’ approach to budgeting can work against best value for money by encouraging spends to be rushed through before the end of a set budget period. Carrying forward funds can be the more astute thing to do.

Leading from the front

Charles Dickens reminded us in David Copperfield that good budgeting sits at the heart of personal satisfaction: ‘Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen pounds nineteen and six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds nought and six, result misery.’

Understanding this simple relationship between money in and money out is also at the heart of financial planning at work that supports what we want to do – and how. Putting our money “where our mouth is” is not just about keeping the business afloat, crucial as that is. It also says something about how we choose to spend that money, our priorities and values, the way we operate and our purpose and goals.

Reframed in that way, perhaps Dickens was right: maybe good budgeting is the unlikely route to true happiness.

Test your understanding

-

Outline the relative pros and cons of zero-based and incremental budgeting.

-

Describe the five core stages of a typical budgeting cycle.

-

Identify three questions you might ask if the figures don’t add up.

What does it mean for you?

-

Consider three types of budget relevant to your current role. What more could you do to understand their purpose and to implement and monitor them effectively?