By adopting a ‘minimum viable product’ (MVP) mindset, whereby we test a core concept before investing too many resources in it, we are better able to identify issues and make positive changes that everyone has a stake in.

What is a minimum viable product (MVP)?

In most start-ups, a company will want to develop its product (or idea for a product) at the lowest cost possible.

First comes the prototype which evaluates the general ‘shape’ of an idea. If that proves sound, they will then need to develop a working version in order to gauge the product’s viability in the market. This is known as a minimum viable product or MVP; essentially, it’s a basic working model with a core set of features that can be used for initial user testing and to gather feedback.

Of course, the size of the 'M' in your MVP depends on your product and market.

‘Minimum’ may still be feature-rich, as long as it’s just enough to accelerate learning while avoiding a waste of time and money. After all, the idea itself may be wrong. And that’s part of what we’re trying to discover.

How can an MVP mindset support business strategy?

Testing at any early stage is a useful way of unlocking honest feedback and customer collaboration.

For example, Google launched its now-ubiquitous search engine with a basic HTML page to see how users reacted to it before developing the product further. This enabled it to identify bugs and potential problems and to gather positive suggestions as to what else might be changed to actively improve the product.

Yet it’s not just large companies that can benefit from having an MVP mindset. As individuals, we can also apply this ‘small steps’ approach to everyday tasks and interactions of all kinds.

But first we have to shrug off the straitjacket of perfectionism and recognise that ‘minimum viable’ is sometimes a lot more useful than ‘maximum vanity’.

What problems can an MVP mindset help to address?

As leaders, we often feel the need to refine our ideas before we share them. So, by the time we ask for input, what we’re really seeking is validation for something fully formed, not truthful feedback that we can actually learn from.

This shuts down the window of opportunity for constructive feedback, bug fixing and positive improvement that gives the MVP phase of a project such value. It can also leave our team members feeling both frustrated and demotivated.

If we don’t invite their input, their only choice is to either get behind our own idea (while having little or no stake in it) or set themselves in opposition to what they perceive as a ‘bad’ idea, even though they could show us ways to improve it.

Neither bodes well. In fact, we know from research that the opportunity to make a positive impact is one of the most significant factors in improving staff motivation – way above money as a driver. So, we exclude our team members at our peril.

Understanding the basic principles

In order to develop an MVP mindset, it helps to understand a few basic principles:

-

Spending time crafting an intrinsically bad idea is a waste of effort, energy and money.

-

Sometimes, progress requires us to embrace uncertainty.

-

However good our ideas may be, we will still have made unhelpful assumptions.

-

All team members must feel safe enough to share their honest feedback.

-

Even the lone genius can benefit from healthy collaboration.

Spending time crafting an intrinsically bad idea is a waste of effort, energy and money

There’s little point investing resources in an innovation that will never fly. Instead of wasting time trying to perfect something on our own, we should invite our team members to help us get there better and faster by bringing their insight to the task.

By involving other people sooner, we are better able to determine which ideas are most worth building upon while gathering the courage to ‘kill our darlings’ – in other words, to ditch the projects that just aren’t right, however much we love them.

To quote Eric Ries, author of The Lean Startup: “The big question of our time is not ‘can it be built?’ but ‘should it be built?’.”

Asking for feedback can help us to reach the right conclusion sooner.

Sometimes, progress requires us to embrace uncertainty

Sharing our less-formed ideas – asking “what if…?” and “how about…?” – means expressing our uncertainty and doubt; this is something we can feel quite uncomfortable with as leaders, especially as we are often required to ‘have all the answers’.

So, it’s important to remember that perfect can be the enemy of good. Rather than polishing our ideas until they shine, we must be brave enough to accept that sharing early means learning fast – and that this can be highly beneficial.

For example, the issues that are invisible to us may be blindingly obvious to our team members – as might valuable improvements.

However good our ideas may be, we will still have made unhelpful assumptions

Sharing ideas with team members at an early stage can also help to differentiate truths from assumptions. The more fully rounded the view, the easier it is to spot unhelpful assumptions and to validate those that are useful.

All team members must feel safe enough to share their honest feedback

If we are to gain maximum value from the feedback we receive, every team member must be comfortable giving the negatives as well as the positives.

A bit like Persil’s “dirt is good” flip on ‘whiter-than-white’ washing powder, we need to convey that ‘problems are good’, because it’s problems that provoke solutions. So, for junior team members especially, we need to create a psychologically safe environment where they feel confident to challenge us.

One way to build confidence is to have team planning sessions where everyone is encouraged to share their worst ideas first. This doesn’t just get a lot of bad ideas out of the way quickly; it is also a great leveller. Plus it can throw up some interesting ideas that are well worth exploring, especially as a bad idea can sometimes have a very good idea on its flipside, if only we have the chance to turn it over.

Even the lone genius can benefit from healthy collaboration

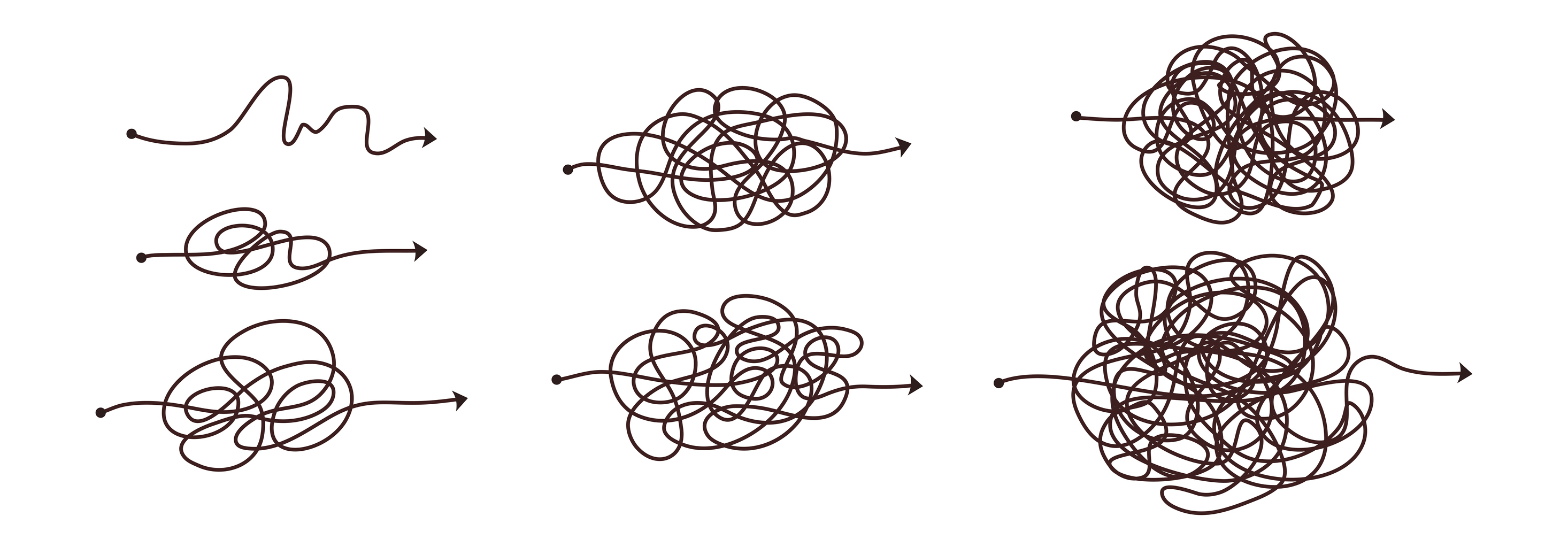

However good our capacity for problem-solving, many of us underestimate how complex projects really are. We see the journey from A to B as a straight line, but more typically it will involve a number of false starts and deviations.

For example, Slack’s founders set out to build an online game and ended up with a hugely popular office messaging app, while Viagra was originally intended to treat chest pain.

By collaborating with others, we are not only better able to identify and fix any glitches but also more likely to find the opportunities that we simply weren’t looking for. And this works best when an organisation has a genuine learning culture that recognises that it’s ok (and sometimes even good) to fail.

Putting an MVP mindset into practice

The key to having an MVP mindset it to take small but valuable steps towards our goals.

This means doing just enough to test our assumptions and gather useful feedback so we can then fix any glitches and make identified improvements before investing too many of our hard-earned resources.

For example, we may be charged with the task of developing a new kind of networking event for our company’s clients – that’s the goal. We could go all out from the get-go, hiring a fancy venue, sorting catering and entertainment, and trusting that our bold ideas make for the perfect ‘finished product’.

But what have we learnt? Might it have been better to first chat to a few clients and get a feel for the type of event they would really enjoy? Or to try out the caterers with a small lunch for colleagues before planning a sit-down meal for 200?

Having an MVP mindset is all about making incremental progress, not finding out too late that we’re up to the dickie bow in bills and bad feeling before the first client has even whispered “I hate jazz…”.

That’s why ‘minimum viable product’ beats ‘my virulent perfectionism’ hands down.

Test your understanding

-

Outline the basic principles of an MVP mindset – and explain why this can add value.

What does it mean for you?

-

Try approaching your next project with an MVP mindset and note how this affects its development.