To make the most of the knowledge we create and acquire, we need cultures where social networks can help best practice to flow freely.

As job titles go, scientist-turned-strategist John Seely Brown’s description of himself as Chief of Confusion might take some beating. By that, he means that he helps people ask the right questions, to invite them to make sense of the constantly changing world around us by not taking things at face value.

JSB (as he’s known) has, in particular, some interesting things to say about technology and how we humans interact with it. So, when he suggests that he “would rather hire a high-level World of Warcraft player than an MBA from Harvard”, he’s likely to get our attention.

It turns out that being a World of Warcraft afficionado might well equip us for one of the great challenges of our age: how we can create, share and harness the knowledge and best practice that underpins so much of the work we do today and promises to be a key contributor to competitive advantage.

According to JSB, World of Warcraft is the very model of a self-supporting, collaborative community, full of people motivated to tackle problems they care about and to share what they know and find out. Through a structure of “guilds”, players group together to come up with, test and share gameplay ideas and strategies. Guilds may be self-organising, but they’re also serious about performance, with structures in place for post-action reviews and iteration.

For JSB, they offer a prime example of how we might all work together to generate and pick up new ideas, to be able to learn faster by doing and sharing things with others.

The concept of these kinds of communities – like-minded people coming together to share and gain knowledge from one another – is not new. Think of the average cross-functional project team working together to overcome a thorny problem. Or an industry-wide trade body pooling expertise across its members to create an industry-wide best practice guide.

What’s different, these days, is that we can’t simply come together for a specific, time-limited or defined purpose, share knowledge and then squirrel it away somewhere for future generations.

Just as those World of Warcraft players face a constantly evolving gameplaying platform, so our world of work requires us to find ways to share knowledge that is itself subject to fast-paced change, or not yet fully formed.

JSB differentiates between the relatively stability of the twentieth century, when our management thinking and structures were designed for predictable and controllable environments characterised by established organisational routines and minimising variances (scalable efficiency) with the “exponential world” we face today, where even our ways of knowing have become outdated.

In knowledge terms, this means moving from stocks of knowledge, where knowledge assets are considered to be authoritative and managing them is about protection and delivery, to a world defined by knowledge flows, where we need to constantly create and share new knowledge that’s tacit or implied rather than explicit (of which more below) in the service of scalable learning.

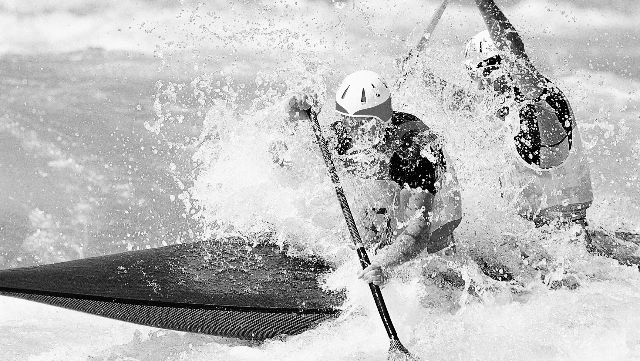

Where once we might have been knowledge management steamboats, setting a course and sticking to it, these days we’re more like whitewater kayakers, rolling and adjusting in a world that’s increasingly fast, radically contingent and hyper connected. Our era is no longer just about deepening individual expertise within a silo, focussing on what we already know. Instead, it’s about participating in and shaping knowledge flows when all around us in in flux.

In this brave new world, how, then, can we make sure that we’re harnessing our very own World of Warcraft guilds to make the most of what we know?

What do we mean by knowledge?

As always, it’s helpful to take a step back and to think carefully about what we mean by “knowledge” and why it’s important that organisations and individuals find effective ways to use it.

It’s been a long time since most of us made our living as artisans, farm labourers or craftspeople who knew and were in control of every step of a process that would shoe our horses, grow cabbages or weave the baskets to carry them in. Since the early days of industrialisation and the rise of the concept of the division of labour, specialisation has been the order of the day, breaking down tasks into their component parts to improve efficiency and drive growth.

These days, it’s generally impossible for any of us – even the most talented CEO – to know everything about our organisations and how they operate. Just as Leonard Read’s famous essay, I, Pencil, reminds us that no single individual knows how to make a pencil, how Dave in Accounts spends his time largely remains a mystery to us, except in the very broadest of terms.

The fact that we continue to make pencils (and invoice our suppliers on time) is down to thousands of individuals building and honing that expertise and know-how over time, and finding ways to communicate and share that best practice for future generations.

But, as organisations become more complex, and we are just as likely to be programming apps as making pencils, how we do that needs to change too. In our knowledge economy, we need to create value out of an organisation’s intangible assets: what we know rather than what we produce. And that means that even our basic understanding of what we mean by knowledge has to be recalibrated.

Knowledge vs information

First things first: knowledge is not the same as information. Information is data that has been processed – but that doesn’t mean that it has meaning or will answer someone’s “how?” questions. It’s only when information is appropriately marshalled that that it becomes knowledge. And that means that it’s tied to people’s experiences, values and beliefs. It’s also contextual, dependent on the environment in which it was gained or is to be used.

The US space agency, NASA, is often lampooned for having to reinvent a process for flying people back to the moon. Didn’t they do this before, we wonder? Surely they know how? But that’s to misunderstand how the knowledge they harnessed back in the 1960s has moved on since then.

Scientists are rethinking and reinventing because they have access to a wealth new knowledge that means they no longer have to rely, for example, on levels of computing power that, these days, would be hard pressed to power a single mobile phone. Knowledge is a living, dynamic thing that’s always changing.

Explicit vs tacit knowledge

Knowledge can also be explicit or tacit (implied). Explicit knowledge is knowledge that can be precisely expressed and explained. It can be codified and understood independently of its originator. Making a pencil might be complex and involve multiple components, but each of those components can be created by following a series of communicable steps (although this does not make explicit knowledge the same as information, as it will change in value and use depending on user and context).

In contrast, tacit knowledge is understood by its holder but often cannot be explicitly explained or codified. It is often based on insight, intuition and experience, and refers to a person’s internal state as well as their ability to complete a task. So, Dave in Accounts may be able to run a sales ledger according to codified accounting rules, but it’s a different matter when his finance director boss uses her years of experience to successfully negotiate new sources of funding for the business.

And, as more and more of us find ourselves paddling JSB’s whitewater kayaks, we’re only going to be increasingly faced with finding imaginative ways to share tacit – or emerging - knowledge that simply can’t be codified or easily recorded.

When tech is not the answer

Time was when the answer to the conundrum of how to manage and share knowledge across organisations was to invest in a shiny new, centralised knowledge management system, a computer system used to gather and store an organisation’s collective intelligence. This kind of tech, the received wisdom supposed, would help us to identify, protect, codify and share best practice, giving us healthy returns and significant competitive advantage.

In many cases, it’s not quite worked out like that. According to Bayes Business School professor, Harry Scarborough, the limitations of knowledge management systems may well be down to an outdated conception of knowledge itself.

He argues that, when knowledge is ‘dumped’ in a central bank, and its ownership is not maintained, it reverts to information, which, as we’ve seen can be difficult to reinterpret and reuse in different contexts. And because knowledge is an intangible and enigmatic, it can, by its very nature, be a difficult commodity to transfer effectively. Centralised storage systems might work for information about explicit tasks and processes, but deep, tacit knowledge about how to get things done is a different matter.

The central paradox of tech-based knowledge sharing is that the more that knowledge is encoded to ease transfer across an organisation, the trickier it becomes to interpret it and apply it to real work situations in various contexts.

It’s a problem reiterated by London Business School’s Freek Vermeulen. He references a study in which the researchers looked at how teams of consultants in a big accountancy firm used documents stored in central databases to help them win new business.

Pretty much across the board, the more the consultants spent time searching these databases, the less likely they were to secure new clients. The researchers concluded that the consultants would have been better off not wasting time trying to wade through historic documents and instead use their own experience to craft more original pitches.

Vermeulen concludes that we need to “shut down” our expensive document databases that are a nuisance, difficult to navigate and can’t really store anything meaningful anyway. Real knowledge, he concludes, “is quite impossible to put onto a piece of paper.”

Towards knowledge flows

If knowledge management isn’t really a technological problem, what can we do instead to encourage people to share what they know?

For Harry Scarborough, knowledge is best generated and shared not through tech or hierarchies, but by informal, social relationships and collaboration. Organisations and individuals alike need to foster networks that help to build connection and provide psychologically safe cultures that enable JSB-style knowledge flows.

Here are five ideas for making that a reality.

1. Beware silos

Gillian Tett, journalist and author of the book The Silo Effect, outlines another paradox of our information age: the fact that we are simultaneously more interconnected and yet more fragmented. This is manifested in everything from political polarisation to organisations endlessly organised into divisions and subdivisions or the hyperspecialisation inherent in complex tech products and services. In short, we live in silos.

Silos are not all bad, says Tett; they help us classify and organise the world around us; they can encourage accountability and drive efficiency; we need expert teams to function in a complex world. But we also need to be alert to their pitfalls: competing teams battling for resources; tunnel vision and mental blindness; poor knowledge flows that create bottlenecks and mean that risks go unchallenged and innovation is stifled.

To master this tricky balancing act, Tett encourages us to think of silos as “a cultural phenomenon”: they might seem natural, but they almost always arise out of rules, traditions and conventions that can – and, in many cases, should – be challenged.

Tett gives the example of the electronics company, Sony, attempting in the late 1990s to replicate the success with their 1970s Walkman. But when they unveiled not one, but two digital audio players in 1999, it was less a sign of eclectic, creative genius than an ominous one of impending doom.

The two devices were the result of Sony’s complex divisional structure and a failure to agree on a single product approach. Their semi-autonomous divisions may have been good for efficiency and margins, but that same autonomy also created cultures where divisions wanted to self-protect themselves against not just their competitors but also other departments. They became less willing to share ideas, to rotate staff. Interaction and collaborate halted, as did experimentation and longer-term risk taking.

This kind of silo mentality made Sony especially vulnerable to a new market entrant where the culture was very different: Steve Jobs and Apple. With just one company running a single P&L, Apple’s engineers brainstormed ideas across product categories. The result: Apple’s iTunes store and its very own portable digital music device, the iPod.

When our systems and structures become too rigid, and silos dangerously entrenched, we can be left blind both to risk and opportunity. Like Scarborough, Tett believes that breaking down silos is about behaviours and mindset. Using approaches from anthropology, she encourages us to be open-minded and curious, stopping to think and interrogate the gap between rhetoric and reality. It’s about more generosity of spirit rather than a sense of inward-looking defensiveness.

She also offers five key ways to keep harmful silos at bay:

-

Keep team boundaries flexible and fluid: rotate staff and create places and programmes where people can “collide” and share.

-

Think carefully about pay and incentives to avoid the problems of internal defensiveness and competition.

-

Create cultures where people are enabled to interpret information differently and are heard. There is more than one way to define knowledge.

-

Keep the way we are organised and operate under review. Focus on consumers and customers and avoid being too rigid. Re-thinking the way we do things can spark innovation.

-

Remember that it’s human imagination that programmes the tech. We’re in charge of the data; not the other way around.

It might sometimes seem easier to stay in our silos and succumb to Tett’s “curse of efficiency”. But being too rigidly streamlined can be a dangerous strategy, leading to the limitations of JSB-style knowledge stocks rather than those knowledge flows.

2. Design work for collaboration and connection

Another of Tett’s stories concerns the pre-2008 financial crisis bankers who hunkered down to create increasingly complex financial products that no-one really understood when, as we now know to our cost, rather more joined-up scrutiny might have been in order. And one of the drivers of this behaviour? Structures and incentive schemes that – as at Sony – mitigated against open and honest collaboration.

In contrast, Morten T Hansen and Bolko von Oetinger chart the success of early 21st-century experiments in corporate collaboration by the oil giant, BP, that made cross-department collaboration a measurable part of people’s jobs.

Rather than relying on central knowledge management systems which, as we’ve seen, are a mixed blessing, Hansen and von Oetinger suggest that we need to focus on behavioural change. Systems may work for the simplest of explicit information or knowledge transfers – like a template or checklist for a simple, stable task or process – but, for more complex, implicit knowledge transfer, we need “direct personal contact” and collaboration.

Their answer is for leaders to adopt a specific type of T-shaped management, one that combines a focus on the performance of their own team or business unit (the vertical bit of the ‘T) with responsibility to share and collaborate across the organisation (the horizontal bit of the ‘T’).

They give the example of business unit heads at BP with two-part job descriptions: responsibility for acting as CEOs of their units, plus explicit expectations that they would spend a significant percentage of their time (up to 15-20%) on cross-unit knowledge sharing initiatives. These manifested themselves in four ways:

- Collaboration with formal peer groups.

- Connecting people throughout the organisation, acting as “human portals”.

- Giving on-request advice to other teams, known as “peer assists”.

- Taking “peer assist” advice from other teams.

More widely, BP credited the initiative with a whole host of positives, including increased efficiency through the easier transfer of best practice, better decision making and the development of new business ideas through the cross-pollination of ideas.

By creating clear incentives for leaders to connect and share knowledge and the structures for that to happen, the company built a more open culture where people could “learn, teach and collaborate” and knowledge flowed effectively through decentralised, horizontal networks.

Research into collaboration between knowledge workers in Australia and China also found job design matters – as does motivation. The researchers found that people were more likely to share when they were autonomously motivated, when they could see the value of sharing rather than being pressured into doing so through controlled motivation to get a reward or avoid sanctions.

Levels of collaboration were also higher among people with cognitively demanding jobs and those with more autonomy. Designing jobs that allow people the freedom to want to discuss and share is a route to improved connection.

3. Bottom up: communities of practice

JSB’s World of Warcraft guilds are a great example of networks that come together organically to find, create and share knowledge, also known as communities of practice (CoPs).

First identified by cognitive anthropologist Jean Lave and educational theorist Etienne Wenger in the 1990s, communities of practice are formed by groups of people – both within and between organisations and, increasingly these days, virtually – who have a common interest in a particular area of knowledge or domain. By the process of sharing knowledge and experience, group members build a community where they forge relationships and learn from one another.

CoPs are also about practice. They collaborate to solve problems, creating and codifying tacit knowledge into best practice – and, as with those World of Warcraft guilds, testing and reiterating that best practice too.

Communities of practice help to bridge the gap between knowing what and knowing how. And, like those Australian and Chinese knowledge workers, because their members are highly motivated to share knowledge in their domain of expertise, they are more inclined to be collaborative.

CoPs can evolve naturally because of members’ common interests or can be created deliberately. Their development depends, though, on internal leadership validated from within the community itself: it can’t be imposed from above or outside. That doesn’t mean that they’re a free-for-all; as with those WoW guilds, it’s important to:

- define the scope: what’s the knowledge domain?

- bring together potential members: who has the necessary expertise and experience?

- identify common interests and needs: what issues are members interested in and motivated to solve to create a sense of community?

- clarify the purpose and mission of the community

- sustain interest by growing the community and constantly developing and creating new bodies of knowledge and best practice.

CoPs need enough support and guidance to make sure they’re useful, but without creating so much structure that might threaten the open, informal relationships and sharing that are fundamental to their effectiveness. The need to be communities, not silos.

4. Make it social

In her TED Talk, All work is social, entrepreneur and author Margaret Heffernan tells the story of her first software company. She had employed some of the most brilliant engineering minds she could find, but something was missing. It was only when people stopped being totally focussed on their work, spent time together and got to know each other that the company developed some momentum.

For Heffernan, successful team working and knowledge sharing is all about this social glue. It’s about social sensitivity and empathy and everyone feeling able to contribute, “cultures of helpfulness” driven by people knowing and caring about one another.

She points to the Swedish idea of Fika, often translated as "a coffee and cake break", but, in reality, much more than that. Fika is about “collective restoration”, making time to pause and for other people. It’s not about the snacks; it’s about the connection.

Like CoPs, Heffernan believes that people are motivated by the bonds of loyalty and trust we develop together, our social capital. When we encourage social capital at work, we can build creativity and resilience – and the understanding and candour we need share, support and challenge each other beyond our silos.

Pharmaceutical company Astra-Zeneca proved that enabling connection and collaboration can also be fun. To help people access the vast experience and expertise of their leading scientists, they created Top Trumps-style posters and cards to help raise awareness of that expertise and where it could be found.

By including a photo and some ice-breaker information (one top scientist was credited with being an expert on German beer), the cards helped people to start conversations, to get to know one other. A gimmick, perhaps, but one that has made their scientists more approachable and helped others to access their huge knowledge assets and bring this expertise into their own projects.

5. Consider workplace workspace

Bell Labs is a famous name in the pantheon of US scientific research institutions, responsible for many of the innovations that have defined our lives for the best part of a century. It did so, of course, by attracting and deploying the finest minds, but it’s also famous for its culture of collaboration. And this sense of connection was also fuelled by the physical environment in which these top minds worked.

At Bell Labs’ HQ in New Jersey, all of the lab spaces connected to a single corridor – which was the length of two sports fields. People were bound to meet there, leading inevitably to spontaneous and meaningful interactions. Author, Jon Gertner, suggests that “a physicist on his way to lunch in the cafeteria was like a magnet rolling past iron filings.” Employees were also instructed to work with their doors open to promote the free flow of ideas.

The lessons have not been lost of other research organisations. For example, London’s Francis Crick Institute brings together more than 1,000 scientists in a building similarly designed to encourage collaboration. As biomedicine has become more interconnected with other scientific disciplines, the Institute has created a physical environment that helps researchers to work beyond traditional disciplinary boundaries.

“Interest groups” bring together researchers to share insights and plan activities in areas of common scientific interest, working in collaboration spaces at the centre of each of the building’s floors. It’s an environment deliberately designed to foster impromptu conversations, idea sharing and connection.

Gillian Tett also describes how a rapidly growing Meta (then known as Facebook) used architecture as one of its silo-busting weapons. Its headquarters at Menlo Park in California was designed explicitly to encourage people to collide and share, from its open spaces and glass-walled meeting rooms to interconnecting walkways and the central Hacker Square. It offers a means to encourage communication to move horizontally, even serendipitously, instead of via a rigid hierarchy.

For those of us struggling to concentrate in a standard open-plan office, this might all seem a bit aspirational; even the Francis Crick building has been accused of being too noisy. We know, too, that open plan offices can actively discourage collaboration, not just because of the noise and distractions but also because of the sense that speaking up or interrupting someone in such a public space can be intimidating.

Many people find working in such an environment stressful. On any given day, a large percentage of our colleagues will be taking refuge in set of noise-cancelling – not to say collaboration killing – headphones.

Software company Basecamp proposes that we need to give up on trying to make open plan offices collaborative spaces. Instead, we should see them as libraries, using Library Rules to keep them as a “library for work rather than an office for distraction. But they also know that they need to have spaces where people can engage in “full-volume collaboration”, separate Team Rooms where people can meet and work together.

The lesson is: open plan offices are efficient in many ways; just don’t expect them to facilitate collaboration. We need a range of spaces at work - including social spaces – to drive knowledge and best practice sharing.

Many years before NASA flew to the moon, Sir Isaac Newton also looked to the heavens and saw further than others because, following conversations with his scientific colleagues, he “stood on the shoulders of giants”.

Our knowledge economy requires us to make the most of the knowledge we create and acquire, to keep it circulating so that others can use, update and add to it. Author and teacher, Seth Godin, talks of our productivity being a “productivity of connection” and actively encourages us to steal his ideas – provided that we use them to come up with something better and keep looking for the next thing worth stealing.

To keep that knowledge flowing, we all need to work out ways to stand on the shoulders of our colleagues – and to offer them ways to stand on ours too.

Test your knowledge

-

Explain the difference between John Seely Brown’s stocks of knowledge and his knowledge flows.

-

Outline how knowledge differs from information.

-

Identify two reasons why silos are bad for best practice sharing.

What does it mean for you?

-

Consider Gillian Tett’s five ways to keep silos at bay. Choose one or two and think about applying them in your own context. How might they make a difference?