Swedish psychologist, K Anders Ericsson challenges the view that the top performers are ‘born not made’.

Back in 2008, when Malcolm Gladwell published his book Outliers, his views on what makes someone really good at something made us all sit up and take notice.

Greatness, according to Gladwell, requires time; at least 10,000 hours of practice is the key to performing at the top of our game, opening up the prospect that, with enough hours of practice under our belts, we might all become the next Roger Federer or Yehudi Menuhin.

It’s not that simple, of course. Since then, his 10,000-hours thesis has been dogged with controversy and criticism, and Gladwell has often been forced to defend and fine-tune his argument as a result.

But one thing remains: we’re endlessly fascinated by people who are very good at what they do –sportspeople, musicians, even top business leaders. And it seems we’re also fascinated by what makes them tick, how they’ve achieved their greatness – perhaps in the hope that we can learn something along the way too.

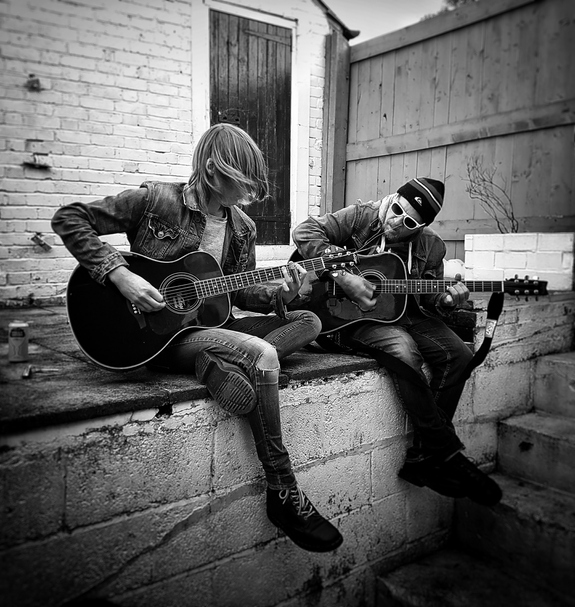

While Gladwell popularised the idea that practice really does make perfect, the credit for a lifetime’s work on expert performance and deliberate practice properly belongs to Swedish psychologist K Anders Ericsson. And the good news is that Ericsson’s work, challenging the view that the top performers are ‘born not made’, has a positive message for us all. The ‘gift’ we all possess is the adaptability of the human brain and body, which, with the right sort of training and practice, can most definitely lead to better performance.

Going beyond: stepping outside our comfort zones

Whether by establishing a new regime of regular jogging, or pushing ourselves to learn something new, this adaptability is our friend: with time and practice, we will adapt and establish a new normal. The more – and crucially, the better – we practise, the more we build up what Ericsson calls the mental representations to improve our level of skill.

Ericsson differentiates between three different types of practice:

- naïve practice – and its more intentional and focused cousins

- purposeful practice

- deliberate practice

Naïve practice

If someone has been driving for more than 20 years, effectively ‘practising’ every day while driving to work, we might assume that person will be a more expert driver than someone who has only recently passed their driving test. Wrong, says Ericsson. This type of practice he calls naïve practice, where we reach a basic level of competency – and then our performance reaches a plateau.

Naïve practice is what we do most of the time and it doesn’t lead to improvement. We repeat what we’ve done before, but stay in our comfort zone; we don’t challenge ourselves to adapt and change.

Purposeful practice

To improve our skill level, we need a more focused and deliberate approach – what Ericsson calls purposeful practice. Being more intentional creates a new normal beyond our comfort zone, leading to improved performance.

There are four characteristics of purposeful practice

1. Well-defined, specific goals – our purpose

2. Focus – high concentration and no distractions

3. Feedback – the more immediate the better

4. Pushing beyond our comfort zones – most important of all, we need to adapt and create that new normal

Deliberate practice: Ericsson’s ‘gold standard’

While following the elements of purposeful practice will lead to improvement, it might not lead us to ‘gold standard’ expertise.

The difference between deliberate and purposeful practice is that deliberate practice is both purposeful and informed. This means that it needs to take place in a field that is already well developed, where, according to Ericsson “the best performers have attained a level of performance that clearly sets them apart from people who are just entering the field”.

Perhaps that’s why deliberate practice is often closely associated with sports such as golf or chess, or with high-level musical performance (some of Ericsson’s earliest research was with classical violinists). It also needs a teacher or coach who has an understanding of what this expertise means. Ericsson again: “Deliberate practice is purposeful practice that knows where it is going and how to get there.”

So, deliberate practice might be expressed as follows:

The four components of purposeful practice + objective standards for success + expert coaching = deliberate practice.

So what of Gladwell’s now infamous 10,000 hours? Ericsson is not convinced. Sure, reaching the top requires a lot of practice, but it’s impossible to put a figure on it; like so much else, it depends on context.

And for us ordinary, non-elite mortals, who are not operating in the right kinds of environments? Ericsson’s advice is “get as close to deliberate practice as you can…this often boils down to purposeful practice with a few extra steps: first, identify the expert performers, then figure out what makes them so good, then come up with training techniques that allow you to do it, too”.

In summary, then, here’s the Ericsson blueprint for success:

-

Find the best performers at the skill you want to acquire.

-

Work out what they do to make them so good.

-

Create a practice regime that allows you to do the same.

-

Practise purposefully: set clear goals; focus; take feedback on board; and, most importantly, push yourself past your comfort zone.

Test your understanding

-

Describe the three types of practice pinpointed by K Anders Ericsson.

-

Explain why 'deliberate practice' is the gold standard.

What does this mean for you?

-

Try improving a specific skill with deliberate practice – and reflect on your progress.