To learn, grow and thrive, we must navigate the cult of authenticity and experiment with different leadership behaviours.

“Strange fascination, fascinating me / Changes are taking the pace I’m going through” (David Bowie, Changes)

In a world of phoniness and filtered fakery, we are all striving for authenticity – ‘safe’ in the knowledge that effective leadership requires a healthy alignment between internal beliefs and external behaviours.

Today’s business heroes are genuine, transparent and self-aware, showing consistency of style and making life decisions that reflect their values and personality. Their congruence earns trust and aids communication, rendering them credible and impactful.

“Be yourself, everyone else is already taken,” advised Oscar Wilde – whose sayings are renowned for their incontrovertible truths. However, he also warned that “the truth is rarely pure and never simple”.

Given this, it is perhaps advisable to heed the cautions of London Business School’s Professor Herminia Ibarra, who asserts that “the way we think about authenticity poses a real danger to our capacity to grow and learn”.

For Ibarra, personal evolution requires us to play with our self-concept – a process undermined by a hyper-focus on a defective definition of authenticity.

“I think we have reached peak authenticity,” she reported in a TED Talk in 2018, observing the steep proliferation of articles, books and workshops on the subject over the past decade, and a following that borders on the cultish.

Desperately seeking sincerity

Our preoccupation with authenticity is visible in our passion for ‘vintage’, our suspicion of gentrification, our anxieties around ‘cultural appropriation’, and even, perhaps, in our weakness for conspiracy theories.

They attest to a longing for ‘realness’ in a world of mass production, digital manipulation, scripted ‘reality’ shows and surgical enhancement. We demand authenticity not only in our brands and leaders, but in our wider role models, calling out those that fall short.

For example in 2020 Hilaria Baldwin, the Boston-born wife of US actor Alec Baldwin, came under fire for ‘misrepresenting’ her Spanish heritage and adopting a ‘fake accent’ – claims that cost her at least one big brand deal. And in 2013, even music icon Beyoncé provoked wrath on social media for lip-syncing The Star-Spangled Banner at president Obama’s second inauguration.

Being ‘fake’ has become the eighth deadly sin, and an accusation to fear.

To avoid such allegations, film director Penny Lane published footnotes to her animated documentary Nuts! (which explored the life of eccentric genius Dr John Romulus Brinkley, who built an empire in Depression-era America with a goat’s testicle impotence cure and a million-watt radio station). She explained that, by doing so, she hoped to “make interesting headway in a significant ethical debate around truth and manipulation in documentary”.

Ironically, of course, the very quest for authenticity may lead to contrivance, as evidenced by the crafted ‘mistakes’ becoming prevalent on social media service TikTok. Less polished videos are considered more ‘real’ and therefore more watchable – encouraging sharp practice in the pursuit of ‘likes’.

It figures that this is a networking platform beloved of teens. Young people, in particular, are champions of authenticity, with Gen Z (born between 1995 and 2010) characterised as ‘True Gen’ in a report by management consultants McKinsey. In fact, this argues that “the search for the truth is at the root of Gen Z’s behaviour”.

However, tellingly, it adds that, for Gen Z “the key point is not to define themselves through only one stereotype but rather for individuals to experiment with different ways of being themselves and to shape their individual identities over time.”

“In this respect, you might call them ‘identity nomads’,” it states.

Barriers to personal evolution

Gen Z’s interpretation of authenticity echoes Ibarra’s belief that to develop as leaders, we must adopt a flexible mindset to ‘try on possible selves’.

Highlighting “the authenticity paradox”, she explains that defining authenticity too narrowly can lead to a rigid sense of self, leaving little room for development. This becomes a problem when we reach “what got you here, won’t get you there” transition points that require personal evolution.

Because going against our natural inclinations can make us feel like impostors, we tend to latch on to authenticity as an excuse for sticking with what’s comfortable; however, few jobs allow us to do this for long. At a time of exponential change, standing still is not really an option.

Ways in which an overly rigid definition of authenticity can hold us back include staying true to a single, fixed sense of self (which can easily become an anchor rather than a compass), disclosing our every thought and feeling, even when this runs counter to situational demands, and making decisions based on values that were shaped by past experiences rather than current requirements.

Common situations in which leaders grapple with authenticity include taking charge in an unfamiliar role. For example, an intimidating promotion might encourage us to lean on our ‘authentic characteristics’ of honesty and collaboration, regardless of whether these equip us to balance the tension between authority and approachability.

Confessing our nerves to new colleagues, and requesting their support, may show congruence with these traits, but it could also undermine our credibility. Being authentic does not mean being an open book.

Similarly, when selling our ideas (or ourselves), we may cleave to our ‘authentic’ communication style – perhaps presenting positive results via the simplicity of data rather than indulging in the ever so slightly duplicitous ‘theatrics’ of big-picture storytelling. However, since leadership usually involves pitching ideas to diverse stakeholders, gaining buy-in becomes a key part of the role and may involve adapting our communication style to our audience.

In addition, leaders often fail to process negative feedback, convincing themselves that their failings are part of their ‘natural style’, and the inevitable price of being effective, rather than something to acknowledge and address. Over time, this reduces their influence, leaving them stuck in the rut of their ‘authentic’ behaviour.

Think former UK prime minister Margaret Thatcher, who failed to recognise her poor listening skills and intolerance of dissension, only to find herself ousted by her own ministers. The personality traits that got her successfully to that point in her career, as Ibarra might add, weren’t enough to keep her there.

Relying on innate personality can be a mixed blessing, as Deborah Gruenfeld and Lauren Zander point out in Authentic Leadership can be Bad Leadership.

“Acting in a way that feels truthful, candid and connected to who you really are is important, and is a leadership quality worth aspiring to,” they write. “On the other hand, being who you are and saying what you think can be highly problematic if the real you is a jerk.”

Becoming a high self-monitor

Rigid self-concepts may result from a reliance on introspection, which can reinforce outdated views of ourselves. Developing ‘outsight’ – “the valuable external perspective we get from experimenting with new leadership behaviours” – can help us to break free. Thinking and introspection should follow experience, not vice versa – especially in times of transition and uncertainty.

To gain outsight, we must make changes in our jobs, our networks and ourselves; for example, tweaking, expanding and redefining what we do and breaking out of silos, networking intentionally and strategically, rather than relying on the people closest to us (or most like us), and stretching ourselves beyond the boundaries of who we are today, experimenting with different roles and approaches.

From her research, Ibarra concludes that the moments that most challenge our sense of self are also the ones that can teach us the most about leading effectively; good leaders “evolve with experience, discovering facets of themselves they would never have unearthed through introspection alone”.

Insights into this can be gained from psychological profiles identified by social psychologist Mark Snyder, whose Self-Monitoring Scale informs how leaders develop their personal style, measuring the extent to which an individual has the will and ability to modify how they are perceived by others.

While ‘high self-monitors’ handle social situations by fitting themselves to the context and playing a role, ‘low self-monitors’ do what they want, expressing who they are and showing other people their true inner self.

Snyder’s high self-monitors keep trying on different styles like new clothes until they find a good fit for themselves and their circumstances.

Their flexibility means that they often advance rapidly, while low self-monitors (or “true-to-selfers”) may remain stuck, since they lack the natural ability of their ‘chameleon’ counterparts to adapt to the demands of a situation without feeling fake.

Growing adaptively authentic

Developing our own “adaptively authentic” style, then, means increasing our outsight and experimenting with different leadership approaches in order “to figure out what’s right for the challenges and circumstances we face”.

To help achieve this, Ibarra suggests:

Learning from diverse role models.

Growth necessarily involves some form of imitation, but borrowing selectively from a range of people (rather than one individual) will create our own leadership ‘collage’, which can be modified and improved. In Ibarra’s research, she noted that ‘chameleons’ consciously borrow styles and tactics from successful senior leaders, learning through emulation, while true-to-selfers have a harder time with imitation in the absence of a perfect role model.

Working on getting better.

Setting learning goals (rather than performance target) shifts our focus to the value of experimentation. It involves stretching the limits of who we are by doing new things that make us uncomfortable but help us to discover whom we want to become. Because we don’t expect to get everything right from the start, we stop trying to protect our comfortable old selves from the threats that change can bring.

Constantly revising our ‘story'.

As we grow, our leadership identity must grow with us. This requires us to jettison outdated self-concepts and draw on personal narratives that fit our circumstances as we take on new challenges. “Try out new stories about yourself, and keep editing them, much as you would your résumé,” Ibarra advises.

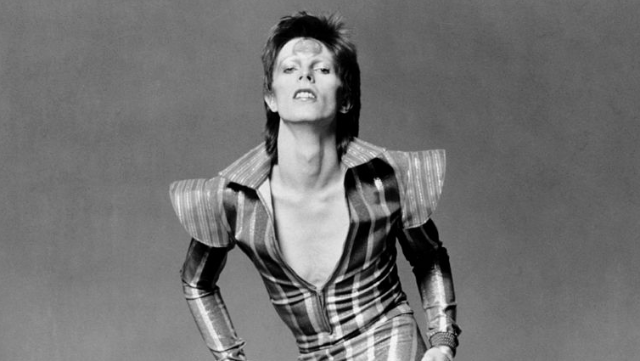

Perhaps the perfect embodiment of this concept is English music legend David Bowie, a renowned shapeshifter, famed for his curiosity and continual reinvention. He experimented throughout his career with fluidity in music, gender, sexuality and fashion, deliberately immersing himself in different media, genres and cultures as part of his creative process.

For example, he adopted many elements of Japanese culture into his stage performances, studying dance with a British performance and mime artist who was heavily influenced by the traditional kabuki style, and learning how to apply kabuki make-up.

As well as painting, sculpting and writing in his spare time, he also explored Buddhism – drawn to its doctrine of 'non-self', which teaches that there is no unchanging, permanent self, soul or essence in phenomena.

Being creatively insecure, and afraid of stultifying within his comfort zone, Bowie often reimagined himself completely from the inside out, creating alter-egos (from Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane to The Thin White Duke) and inhabiting his characters on and off-stage.

“He made a fetish of outpacing his public, releasing records rapidly and shedding personae,” stated a tribute in the FT, published shortly after his death in 2016. “The frequent changes in style and appearance were motivated less by novelty than restlessness, filtered through a consciousness that could see deep cultural connections and was bold enough to attempt to articulate them.”

His hit single Changes, recorded in 1971, summed up this ethos, describing the compulsive nature of artistic reinvention, with lyrics referencing “the stream of warm impermanence”. “Turn and face the strange,” he urged us all.

Ultimately, sticking to what brought him early success would have undermined Bowie’s creativity and curtailed his artistic evolution, in the same way that clinging to our ‘authentic’ traits – and a flawed perception of authenticity – can limit us as leaders, where experimentation enables us to develop and grow.

Such personal exploration amounts to ‘fast prototyping’ with ourselves, as part of a life-long journey of self-actualisation. For Ibarra, it requires the kind of playful frame of mind that Bowie demonstrated, and an understanding that it’s ok to be inconsistent from one day to the next.

“That’s not being a fake,” she concludes. “It’s how we experiment to figure out what’s right for the new challenges and circumstances we face.”

Test your understanding

-

Describe what Herminia Ibarra means by 'the authenticity paradox'.

-

Explain how 'high self-monitors' differ to 'low self-monitors'.

What does this mean for you?

-

Play with developing your own 'adaptively authentic' leadership style, following Ibarra's three suggestions.