Our emotions play a major role in our thought processes, decision-making and individual success. Understanding and deploying them appropriately at work makes us be better colleagues and leaders.

A few years ago, MI6, the UK’s Secret Intelligence Service, posted a recruitment advert on the parenting website Mumsnet, attracting numerous applications and a healthy dose of publicity.

This indicated not only an admirable attempt at workforce diversification, but also an acknowledgement of what it takes to excel in the modern world of work.

In an interview, MI6’s head of recruitment explained that intelligence officers need a blend of interpersonal skills.

A source quoted elsewhere added that they were looking for people with a real passion for human interaction, understanding others, and dealing with the complex nature of human relationships – a basket of skills that might sit under the umbrella term: emotional intelligence (EQ).

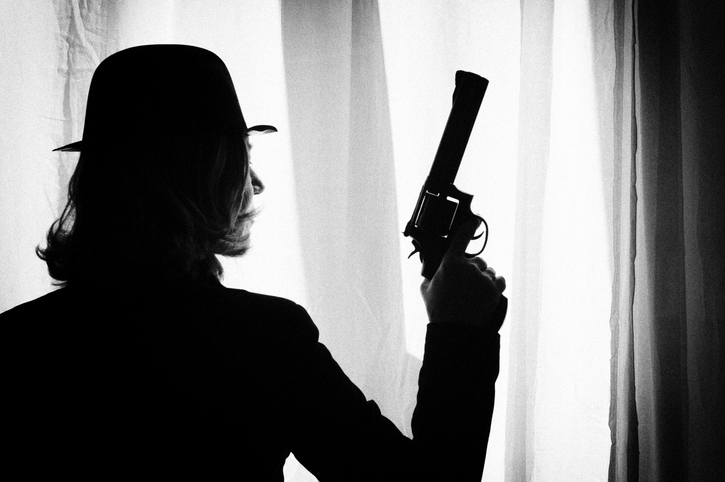

James Bond, they joked, would probably not, these days, be successful in joining the intelligence service, if he were to apply.

But while emotional intelligence is gaining traction as a recognised skill set, this doesn’t mean that our workplaces are awash with emotionally intelligent leaders. We’re far more likely to find ourselves sitting opposite The Office’s David Brent than Mahatma Gandhi in our next 1-2-1.

Knowing about EQ is one thing; really understanding it and integrating it everything we do at work is quite another. The James Bonds of this world can be a remarkably resilient bunch, even today.

From Plato to Goleman

The phrase ‘emotional intelligence’ only entered common parlance relatively recently, becoming a formal area of psychological study – and popularised by psychologist, Daniel Goleman - in the 1990s.

In Goleman’s bestselling 1995 book Emotional Intelligence, he defines EQ as “the ability to identify, assess and control one's own emotions, the emotion of others and that of groups”.

But the sense that our emotions affect our actions and motivations is far from new.

Around 2,000 years ago, the ancient philosopher Plato wrote that “all learning has an emotional base”, while Aristotle showed his innate EQ when he acknowledged that, while anyone can be angry, “to be angry with the right person, to the right degree, at the right time, for the right purpose, in the right way” is much less straightforward.

In other words, to harness powerful emotions, we must be able to draw on our own judgement, self-awareness and self-discipline in the heat of the moment: no mean feat.

More recently, various thinkers have explored the idea of EQ in a bid to articulate it more overtly, for example:

-

In 1920, American educational psychologist Edward Lee Thorndike talked of “social intelligence”being “the ability to understand and manage men and women... [and] to act wisely in human relations”.

-

By the 1950s, Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs allocated a raft of emotional needs to its upper echelons.

-

In 1983, Harvard psychologist Howard Gardner introduced the concept of multiple intelligences, including ‘interpersonal’ and ‘intrapersonal’ intelligence.

However, the term was officially coined in 1990 by American psychologists John Mayer and Peter Salovey, whose landmark paper, Emotional Intelligence, defined it as “the ability to monitor one's own and others' feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them, and to use this information to guide one's thinking and actions”.

Enter Goleman

Building on Mayer and Salovey’s pioneering work, emotional intelligence is now synonymous with Daniel Goleman, a former science journalist for The New York Times, who popularised it to the extent that he is often regarded as the ‘father of EQ’ (or EI, as he prefers to call it) – even though he borrowed the term (with permission) from Mayer and Salovey for his first book.

Goleman’s starting point is that we should not view IQ as the sole measure of ability, arguing that our emotions play a major role in thought, decision-making and individual success.

IQ tests, Goleman believes, are designed to screen candidates based on their ability to process information, rather than their likelihood of success. He even goes as far as to describe IQ merely an “entry-level requirement”, especially for leaders.

Goleman has since been integral in creating a global movement around emotional intelligence, whether writing further books and academic papers, appearing on Oprah or organising a series of intensive conversations between scientists and the Dalai Lama. He’s a passionate proponent of getting EQ programmes into all schools and factoring it into healthcare.

And, of course, he sees EQ as crucial in the world of work, emphasising direct ties between emotional intelligence and measurable business results.

EQ, competence and performance

Goleman’s research suggests that emotional competence is twice as important as IQ or technical competence for jobs at all levels, whether we’re dealing with customers, contributing to a project team or managing investors or funders.

Studies have shown the tangible benefits of working on our EQ, not just for us as individuals, but for the teams we lead and the organisations we work for.

When Coca-Cola trained sales leaders in emotional intelligence, participants exceeded their performance targets by 15%. Leaders who did not develop emotional capabilities missed their targets by the same margin.

Similarly, a three-year study of AMADORI, a supplier of McDonald’s in Europe, assessed the links between emotional intelligence, individual performance, organisational engagement, and organisational performance.

Emotional intelligence was found to predict 47% of the variation in managers' performance management scores and was also massively correlated with increased organisational engagement. Plants with higher organisational engagement achieved higher bottom-line results, building a link between EQ, engagement and performance. During this period, employee turnover also fell by almost two-thirds (63%).

EQ for leaders

EQ also plays an increasingly important role for leaders, where it’s those interpersonal, and not just technical, skills that set people apart.

The qualities traditionally associated with leadership – such as intelligence, toughness, determination and vision – are insufficient on their own.

Truly effective leaders are also distinguished by a high degree of emotional intelligence.

With a growing acceptance that we don’t leave our emotions at the door when we come to work, and a greater emphasis on wellbeing as a crucial underpinning for performance, the skills we need to develop our EQ are more important than ever.

Not for nothing has the Harvard Business Review called emotional intelligence “a revolutionary, paradigm-shattering idea”.

Goleman’s emotional intelligence domains and competencies

In a seminal HBR article, Goleman explores the four domains he sees as the essence of emotional intelligence:

1. Self-awareness

2. Self-management

3. Social awareness

4. Relationship management

Like self-awareness itself, EQ has two sides.

-

The first two domains are Goleman’s “personal” domains, related to what we know about, and how we manage, our own emotions.

-

The second two domains are the “social” domains, related to what we know about others and how we relate to and influence them.

The four domains house 12 ‘nested competencies’, representing capabilities that support emotionally intelligent leadership, such as adaptability, empathy and teamwork.

The framework helps us to understand the elements that will help us to lead in more emotionally intelligent ways, asking us to take a good look at ourselves and others – and then act on what we discover.

A portfolio of skills

Unlike with IQ, there’s no single score that sums up emotional intelligence. Instead, according to Goleman, we have an “EI profile” that reflects our unique personalities and different strengths, motivations, goals and passions.

But we also need to balance these strengths with an awareness of other EQ competencies where we might need to build our skill more deliberately.

It’s very common, for example, for us to consider that we have high EQ if we demonstrate sensitivity, sociability and likability. And, in EQ terms, scoring high on empathy, positive outlook and self-management is certainly important.

But we also need to be able to deliver difficult feedback; have the courage to ruffle feathers and drive change and the creativity to think outside the box – evening out our EQ skills in other areas like achievement, influence and inspirational leadership.

To excel, then, leaders need to develop a balance of strengths across the full suite of EQ competencies. The best EQ improvement plans encourage us to:

-

be honest about our current EQ strengths and weaknesses.

-

consider where we need to build competency.

-

to strengthen any deficient competencies that will help us to achieve our aims.

The dark side of EQ

Despite these kinds of findings, not everyone is wholly in favour of a strong emphasis on EQ. Critics hint at its ‘dark side’, warning that its skills can be used for both good and evil.

Organisational psychologist Adam Grant has expressed concern that when people hone their emotional skills, they become better at manipulating others:

“When you’re good at controlling your own emotions, you can disguise your true feelings,” he said. “When you know what others are feeling, you can tug at their heartstrings and motivate them to act against their own best interests.”

Research by University of Cambridge professor Jochen Menges shows that when a leader gives an inspiring speech filled with emotion, the audience is less likely to scrutinise the message and remembers less of the content – despite claiming to recall more of it.

A study by a research team led by University College London professor Martin Kilduff also looked at the “strategic use of EQ” in organisations.

They concluded that high-EI people (relative to those low on EI) are likely to benefit from several strategic behaviours in organisations, including disguising and expressing emotions for personal gain, using misattribution to stir and shape emotions, and controlling the flow of emotion-laden communication.

Machiavelli would no doubt have approved.

Elsewhere, there have been warnings that low scores on emotional intelligence tests reduce hiring potential as well as job retention, and could alter an individual’s career track, even if they are successfully completing their job requirements.

This kind of focus on EQ is of particular concern for people with (disclosed or undisclosed) autism spectrum disorders, attention deficit disorder or many mental health conditions, and, it has been argued, could even derail some diversity and inclusion efforts.

Heed the debate

Just like any test or diagnostic, we need to guard against over-confidence in EQ’s value as an assessment tool. Critics question the legality (and ethics) of implementing across-the-board EQ testing, and point to the potential stigmatisation of those who do not score highly.

Some cynics go as far as to disagree that EQ is an intelligence of any kind, calling it “a hallucinatory desire to break down feelings into a math equation”.

Others feel that studying it is simply reinventing the wheel, arguing that emotional intelligence is no more than general intelligence plus a mix of the big five character traits by a different name.

Such debate is healthy within a relatively new branch of psychology and, given the growing inclusion of EQ in school – as well as leadership – programmes, it is certainly important to be aware of, and understand, any negative consequences.

However, it’s also clear that the competencies and skills associated with emotional intelligence (however we describe them) can bring a wide range of benefits, from improved relationships to increased achievement and better psychological wellbeing – all crucial elements of a leader’s toolkit.

The ability to know and manage ourselves and to create and manage relationships with sensitivity and purpose are important skills for anyone at work today; for leaders, they are essential.

There is little doubt that leaders with a higher degree of EQ are more able to recognise the impact they are having on their team, to understand how to get best out of others and to foster deeper and more fulfilling relationships with their colleagues. And there’s also increasing evidence that having more emotionally intelligence workplaces drives performance.

Some commentators might predict an imminent future where AI in the workplace will become just as ‘emotionally’ intelligent as humans (if not more so), but that future has not yet materialised.

For now, human skills such as influencing, persuading and social understanding - which cannot (as yet) be replicated effectively by our robot colleagues – remain disproportionately valuable. We can safely rely on the need to keep developing those all-important people skills that form the cornerstone of effective leadership.

Test your understanding

-

Outline Goleman’s four EQ domains,

-

Identify two criticisms of the theory of EQ.

What does it mean for you?

-

Reflect on the balance of EQ competencies you currently have. Which competencies might you need to develop more to boost your EQ further.