Motivating our teams to do the best job possible is far from straightforward. Understanding what motivation is, and the conditions it needs to flourish, is a good starting point.

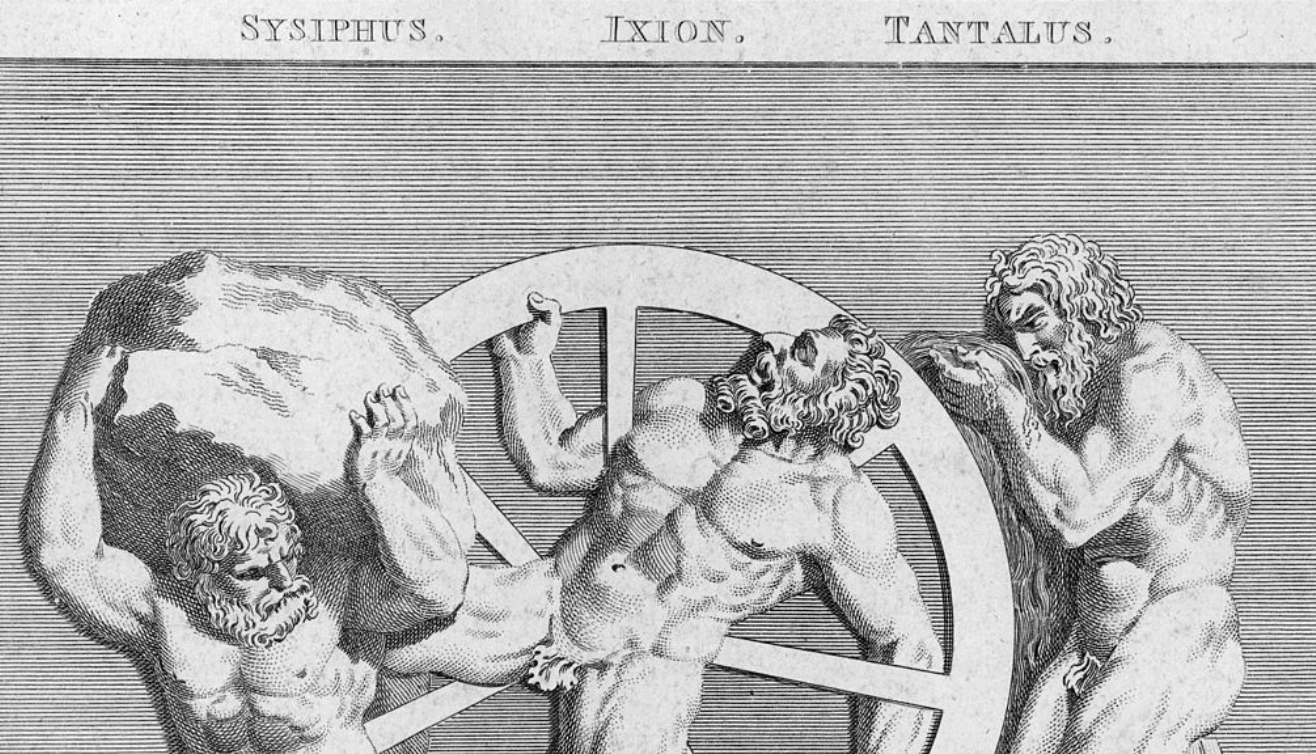

The Greek myth of Sisyphus has often been invoked as a metaphor for the relentless grind of the average workplace. Just like the unfortunate king of Corinth, forever condemned to keep rolling a heavy stone up a hill, only to have it escape him and roll to the bottom each time, it can feel like we’re pushing uphill every day too.

Getting paid at the end of each week or month might feel like scant reward for work where we might feel disconnected and unappreciated, a demotivated cog in that machine rather than a valued colleague able to make a positive difference.

When psychologist, Dan Ariely, wanted to find out why people might be more or less motivated at work, he had a hunch that things are a lot more complicated than simply paying people to show up. So, he invoked the spirit of Sisyphus to test his instinct. In an experiment, he paid people decreasing amounts of money to build Lego Bionicle figures until – unsurprisingly – participants decided it was no longer worth their while.

But that was not the whole story. Ariely also created two different sets of conditions for the experiment. In the first (his meaningful condition) finished models were taken away and hidden before being dismantled. In the other (his sisyphic condition) the models were dismantled as soon as they were built and in front of the builders.

This may seem like a fine distinction, but it still made a difference: the first group made an average of 11 Bionicles; the second group only seven. Both groups knew that their models would not last forever, but even seeing the results of their efforts for a short time improved performance. And while the people in the first group who claimed to love building Lego figures stayed the course for longer, this was not the case for group two.

Their love of Lego was effectively snuffed out by the demotivating environment they worked in.

It's a sobering thought. If such small margins can make a difference to how people feel about even a simple task, what does that mean for leaders who want to motivate people to do their best at work? And what exactly is motivation, and how does it work?

Ariely’s work on motivation sits alongside decades of thinking about what motivates people to turn up for work every day and do a good job. The American Psychological Association (APA) defines motivation as “the desire or willingness to make an effort in one’s work”.

It speaks to the core of leadership: our ability to influence, to get things done through other people and to maximise everyone’s contribution. In the words of Dwight D Eisenhower, “Leadership is the art of getting someone else to do something you want done because [s]he wants to do it.”

Some thinkers argue that even the sense that we should want to motivate people is “management idiot speak”. Instead, the role of the leader is to find something that’s really worth doing and communicate that in such a way that appeals to people’s sense of purpose. That way, they’ll actively want to join us on the journey.

Here, we might invoke developmental psychologist Jean Piaget and his concept of an “equilibrated state”, a situation that’s set up by two or more people where everyone is participating voluntarily. Piaget believed that when children play pretend games more collaboratively, voluntarily negotiating and playing clear roles, that play is likely to be more sustained and productive.

Similarly, in work relationships, getting people on board voluntarily with a “coherent narrative” about the work and how they can contribute is always going to be more powerful than simply telling them what to do and applying sanctions if they don’t perform.

Enabling people to act in the service of common goals can be tricky. It relies on psychology. It needs us to understand our people as individuals: what motivates one person will not necessarily motivate others. It’s influenced by people’s preferences and dispositions, their abilities, skills and – as Ariely showed us – the context we work in. That can be a lot to take on.

On the plus side, most people want to do a good job at work. But, to do that, they need the right conditions – and to be recognised when they perform and improve. Creating these conditions is part of the psychological contract that underpins relationships between employer and employed and leaders and followers.

The ability to motivate people is closely related to people’s sense of engagement at work. If we can motivate people, they’re much more likely to feel engaged with, and committed to, our organisations.

So, if we are to achieve a Piaget equilibrated state, where we’re all positively motivated to do our best, we need to understand what motivation is; the factors that influence it and how we can create environments where we all want to make as many Bionicles as possible.

Theories of motivation

Motivation, then, is a dynamic and sometimes elusive quality, which perhaps helps to explain why there’s such a long history of research into how we can motivate ourselves and others.

There is no single theory of motivation, but looking at a range of them helps us to get to grips with what we might need to do to boost motivation in our teams.

Theories tend to compare and contrast two main types of motivation:

-

extrinsic, driven by external factors such as rewards or avoiding sanctions.

-

intrinsic, driven by our own internal needs, such as the satisfaction of a job well done or to achieve personal goals.

Both types have their place but, as Ariely found, simply relying on extrinsic factors like pay may not be enough for everyone in every situation. That’s because motivation is often a whole lot more complicated. And to understand why, we need to go back to the work of an American psychologist and his famous hierarchy.

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

Abraham Maslow's hierarchy of needs theory is based on the idea that people are motivated by the desire to satisfy their human needs. First published in his classic 1943 paper, A Theory of Human Motivation, followed by his 1954 book, Motivation and Personality, it’s a theory of motivation that still underpins thinking about motivation at work today.

Maslow contended that, while everyone wants to strive for “self-actualisation” – the full realisation of our potential, abilities and our appreciation of life – we often fall short.

That’s because the higher-level needs of self-esteem and fulfilment can only be addressed once our more basic and psychological needs have been at least partially met: hence that hierarchy. When we come close to satisfying one need, we’re ready to move up the hierarchy.

Because of those hierarchies, his model is often depicted as a five-stage pyramid:

It might not be possible (or necessary) to fully satisfy a level of need before the next level becomes a motivational force, but it’s hard to move up the pyramid if we get completely stuck at any of the stages. The five stages represent five types of human needs:

Physiological needs

Our most basic need is for physical survival – air, shelter, warmth, clothing. Without that, we cannot function, and all other needs become secondary.

Think about it: If we were to regularly arrive at work feeling hungry and cold, it might be hard for us to focus on anything other than meeting those most basic needs.

Safety needs

Once we feel physiologically safe, we are motivated to focus on security and safety. We want a sense of order and control over our lives, whether that’s in terms of wider society (law and order; schools; medical care) or the emotional and financial security that comes with having a steady job in a safe environment.

For example, that’s why we have a duty of care as leaders to protect our people from health hazards at work, whether that’s defective machinery or aggressive colleagues or customers.

Social needs

We are social beings who need to feel a sense of belonging and connection, whether at work or beyond. If those social needs are not being met, it’s hard to move up to the “growth” sections of the triangle.

Many of us discovered during the COVID-19 pandemic that a lack of connection can be both disorienting and demotivating. Some of us might have moved down the pyramid as a result.

Self-esteem needs

Esteem needs cut two ways: they relate to our own sense of worth and competence (self-esteem) and also the recognition and respect we get from others (social esteem).

If these needs are not met at work, people may feel alienated or withdraw. That’s why we need to create safe environments where people feel heard and can speak up, and also recognise people’s efforts and achievements.

Self-actualisation needs

At the top of his hierarchy comes self-actualisation, described by Maslow himself as being “the most” that we can be, realising our potential, seeking personal growth and looking for challenges and experiences. Self-actualisers are driven by a sense of values, purpose and potential.

Even when people achieve self-actualisation at work, we need to help keep them there, offering the right kind of climate for them to continue to learn, grow and develop.

Maslow’s thinking has been challenged many times since his work was first published, whether for a lack of scientific rigour or claims that needs simply don’t follow such a straightforward hierarchy. Even Maslow himself conceded that needs are complex and not the same for everyone.

For example, living in extreme poverty does not necessarily preclude the need for social connection; our needs may be different depending on external circumstances or individual differences; our behaviour might also be determined by more than one need at a time.

But, despite these criticisms, the hierarchy remains a useful reminder that people will inevitably bring their human needs to work with them. And while self-actualisation is within reach of everyone, there are plenty of things that can get in the way.

For example, motivation will be compromised if someone is struggling with basic needs (for example, a housing problem or a bullying colleague). And, at the other end of the pyramid, if we fail to take into account those higher-order needs, all the rewards or sanctions in the world are unlikely to hit home.

Herzberg’s motivation-hygiene model (two-factor theory)

Maslow’s thinking was tested and refined in the 1950s by Frederick Herzberg. In his 1959 book, Motivation to Work, he reported on the results of a large-scale research programme designed to identify the factors that made people feel either good or bad about their jobs.

Herzberg found that these factors fell into two groups:

-

Negative factors relating to the context of jobs, what Herzberg called hygiene factors. These led to job dissatisfaction.

-

Positive factors related to job content. These resulted in job satisfaction.

The key finding in his work is that job dissatisfaction and job satisfaction are not opposites.

So, if we work on the dissatisfaction factors that people find annoying or upsetting – like poor working conditions, unfair pay or dysfunctional teams – we may have less dissatisfaction, but that doesn’t mean people will be satisfied.

Satisfaction relies on a whole different set of motivator factors, such as achievement and recognition or opportunities for learning and challenge. Eliminating dissatisfying job factors may create peace but it won’t motivate people to improve and perform. (It’s worth noting here that by “satisfaction” we don’t mean that people are just coasting along in their jobs; it’s about being pro-actively motivated and engaged).

For example, if someone is being bullied at work, giving them a stretch assignment is unlikely to make them feel positive and motivated. Or if we focus just on sorting out those hygiene factors, we might miss out on the positive motivating factors that can really make a difference to how people feel about their work – and, therefore, how much they’re likely to contribute.

The two sets of factors are separate; we need to focus on both. And we need to make sure those hygiene factors are under control before we jump in with our motivators.

The theory has been criticised for a lack of (proven) correlation between satisfaction and performance and its rather blunt distinctions between the two sets of factors. It also fails to take into account that, when things are going well, people tend to focus on the content of their jobs and, when things are going less well, the context.

But, by focussing on the importance of the work itself rather than just the external factors surrounding it, it paves the way for more contemporary thinking about the motivating power of giving people more autonomy to plan and control what they do every day.

Alderfer's ERG Theory

The criticism that Maslow’s theory is too simple to explain the complexity of human motivation, especially in terms of overlapping (rather than hierarchical) needs, was addressed in 1969 by Clayton Alderfer’s ERG theory of motivation.

Alderfer re-cast Maslow’s hierarchy in terms of just three needs (hence ERG):

-

Existence

-

Relatedness

-

Growth

As with Maslow, at the most basic level, people have existence needs. Our relatedness needs fulfil our need for strong interpersonal relationships. At the growth level, we are looking for personal growth through challenging and meaningful work.

Unlike Maslow, he is clear that the order for pursuing needs is not fixed. Priorities can shift depending on the person and the situation, and as people’s circumstances change.

People can be motivated by needs from more than one level at the same time, and there is no strict progression from one level to the next. For example, at some stages of our careers, we might want more flexibility in our working lives and focus more on our relationship needs rather than growth.

The model also introduces the “frustration-regression” we might feel if our higher-level needs are not met – a cautionary tale, perhaps, for leaders striving for an equilibrated state.

ERG theory reminds us that motivating factors are personal and that we need to address a variety of needs at all three levels at any given time. The priority that people place on these needs is both varied and changeable. That means that we have to mind those existence needs while also encouraging positive relationships and providing opportunities for growth and development.

David McClelland's Human motivation theory (three needs/acquired needs theory)

For David McClelland, people have one of three main driving motivators. In his 1961 book The Achieving Society, he identified these as the need for:

-

achievement

-

affiliation

-

power

We’re not born with fixed motivators; they are learned, depending on our culture and experiences. We may, for example, be more achievement oriented if we grew up in an environment with expectations around high academic achievement. Most people are motivated by a combination of the three needs, although one is likely to be dominant.

The idea is that by understanding what motivates each team member, we can customise our approach to how we set goals, support and give feedback and rewards so that we’re maximising their motivating power for each individual.

People with achievement motivation have a strong need to set and meet challenging goals, like to take calculated risks and appreciate regular feedback on their progress. They often like to work alone.

Affiliators want to belong, to be liked and tend to do along with what the rest of a group wants to do. They are collaborative rather than competitive and shy away from risk and uncertainty.

People motivated by power fall into two groups: those who crave power for themselves, and those who want power for their teams or organisations. People driven by power needs want to control and influence others. They enjoy competition and winning and status and recognition.

As with other needs-based theories of motivation, McClelland’s theory has been criticised for its assumption that everyone has the same universal set of needs (in this case with an in-built cultural bias towards the US too). But it reinforces the message that we need to know what drives each of our team members and, where possible, provide them with what they need to feel motivated.

Process theories of motivation

So far, the theories we’ve looked at relate to what motivation is; the content. Other theories and models look at the process of motivation. Instead of a focus on needs, they look at the psychological and behavioural processes people follow. By looking at these processes, we can better understand the actions, interactions and contexts that motivate people.

It’s worth bearing in mind two process theories that emerged in the 1960s:

John Stacey Adams’ equity theory suggests that people are motivated when they feel their “inputs” (such as the skills, experience and effort they put in) are matched by the “outputs” they receive or experience as a result, like financial reward, praise and recognition.

If people sense that their input outweighs the output, then they’ll become frustrated, unproductive and demotivated.

The theory acknowledges that motivation can be a fragile thing, affected by a range of variables that influence people’s perceptions about their work and organisations. Ideally, we want to find a fair balance to be struck between the wide range of inputs people give and the outputs they receive.

For example, if we have an experienced and skilled team member who is hard-working and committed, able to adapt to changing circumstances and ready to support others, they might reasonably expect to be rewarded not just financially, but also in terms of recognition, respect and opportunities to learn and progress.

People will be motivated if they perceive that the balance is fair. If the balance lies too heavily with the employer, people will become demotivated and even vote with their feet.

Victor Vroom’s expectancy theory explores why people might choose certain behaviours over others. The strength of our motivation to act in a particular way depends on the strength of three expectations:

Expectancy: the extent to which our behaviour or action will help us to achieve a certain outcome: will doing this help me to achieve my goal?

Instrumentality: what the reward associated with that behaviour or action is likely to be: if I do this, how will I be rewarded?

Valence: the value we place on the anticipated reward: do I find the reward attractive?

For Vroom, we unconsciously use these variables to identify the “motivational force” (MF) of each potential behaviour or action and then select the option with the highest MF value. As with equity theory, the idea is that we are motivated by the prospect of a return on our efforts.

As leaders, the theory suggests that we need to create and demonstrate two key links:

-

between high effort and high performance

-

high performance and a positive outcome

This then creates a third think – between high effort and a positive outcome – that will help to motivate people.

Towards self-determination

In his 2009 book, Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, Daniel Pink asks us to question one of the key tenets of needs or satisfaction-based theories: the idea that if we reward someone, we’ll get more of the behaviour we want and, if we punish someone, we’ll get less of the behaviour we don’t want.

He quotes a study from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in which students were asked to carry out a series of challenges in return for three levels of financial reward, often a common form of incentivisation in organisations, even today.

In the study, these extrinsic rewards worked well where the tasks were mostly mechanical and required little thinking or initiative. However, as soon as a task became more cognitively challenging, that link between motivation and reward was broken: in fact, the larger the reward, the poorer the performance.

It's an apparent paradox that even has its own name: the overjustification effect. And its basis? That being rewarded for something can actually decrease our intrinsic motivation to do it. The reward becomes the justification, even feeling a bit coercive, rather than our own internal drive to get it done – with predictable results.

It’s an effect that has made Pink question whether extrinsic motivation is fit for purpose in a world of work defined, for many, as a knowledge economy. Just like Ariely and his Bionicles, those rewards will only take us so far; there are other factors at play that we need to consider. That’s why Pink believes that “carrot and stick” tools for motivation are “so last century”.

But what are those “other factors”?

Enter two American psychologists, Richard Ryan and Edward Deci. In the 1980s, Ryan and Deci developed their self-determination theory (SDT) of motivation, the first big challenge to the dominant belief that the best way to get human beings to perform tasks is to reinforce their behaviour with rewards.

Underlying SDT are two key ideas: that people’s need for growth is essential to their sense of self, and that autonomous (intrinsic) motivation is what really drives us. Specifically, we are motivated to grow and change by three innate and universal psychological needs:

Autonomy. We need to feel in control of their own behaviours and goals.

Competence. We need to gain mastery of tasks and learn different skills. When we feel on top of our game, or are getting to grips with something new, we’re more likely to behave or act in ways that help us to achieve our goals.

Connection or relatedness. We need to experience a sense of belonging and attachment to other people.

For Ryan and Deci, creating the conditions that satisfy these basic needs is a key predictor of positive mental health. We tend to be happier when they we are intrinsically motivated to achieve a goal. It makes us feel more responsible for the outcomes and to focus our time on what we really want to do.

Daniel Pink: Motivation 3.0

SDT underpins Pink’s Motivation 3.0 model. For Pink, human motivation was originally about the struggle for survival. As the world became more complex, a second driver was identified: the desire to earn rewards and avoid punishment. Pink calls this Motivation 2.0.

The problem is that, as we’ve seen, these carrot and stick motivators are increasingly out of step with the modern world of work. They have their place, of course. Like Herzberg, Pink is clear that we need to get our “baseline rewards” (hygiene factors) under control before we have a hope of more positive motivation. And even then, as the MIT study showed, they can work well for more routine tasks.

But, on their own, or if we rely on them in the wrong contexts, they can lead to a range of unintended consequences Pink identifies as his “seven deadly flaws”:

-

They can extinguish intrinsic motivation: that overjustification effect again.

-

They can diminish performance

-

They can crush creativity: “rewards, by their very nature, narrow our focus” rather than encouraging us to lift our heads and think more widely.

-

They can crowd out good behaviour such as wanting to complete a task on its own merits or for the greater good.

-

They can encourage cheating, shortcuts and unethical behaviour: just think of those bankers and the 2008 financial crisis.

-

They can become addictive, offering “a delicious jolt of pleasure at first” – but one that comes to requires “even larger and more frequent doses”.

-

They can foster short-term thinking: if we’re only focused on rewards, we are more likely to make decisions that help us to achieve those rewards, which might not necessarily be in the best long-term interests of our organisations.

Rather than just focussing on the extrinsic, we need to go further. We need an upgrade to acknowledge other factors that influence motivation. Motivation 3.0 introduces us to three factors that, together, create the right conditions for motivation:

-

autonomy

-

mastery

-

purpose

Autonomy

We need to feel that we have a degree of control, of agency, over our work to be most productive. This helps us to retain interest and drives motivation because we feel more like collaborators than cogs.

As leaders, we should “provide ample choice over what to do and when to do it”. We need to provide parameters for work that allow some creative freedom while still moving us towards our goals. This is an important consideration when we delegate tasks. It can also help to think outside the box.

For example, the sandwich and coffee chain, Pret, encourages its employees to indulge in “random acts of kindness”, offering a free cup of coffee to whoever they feel needs or deserves it. The decision about who gets a freebie is left to individual team members, making it a win-win: good for customer relationships and empowering for Pret’s people.

Pink reminds us that self-direction like this is a key to motivation. He gives the example of Australian software company, Atlassian. In a version of the (in)famous Google 20% time, the company encourages its developers to spend a day working on whatever they want once a quarter. These “FedEx” Days (so named because of the need to deliver something overnight) have resulted in innovations and fixes that might not otherwise have been developed.

Mastery

The basis of Pink’s second factor is simple: we tend to be more motivated to tackle and complete tasks we can do well or that interest and develop us. The level of challenge is also important: too hard, and we’re likely to give up; too easy and we can become bored and demotivated. Mastery is about becoming better at something that matters. It requires not just compliance (doing something because we’re told) but engagement (doing something because we want to).

Dan Ariely’s research suggests that that the harder a project is, the prouder we feel of it. He gives the example of the IKEA effect. We might curse those flatpacks, but once we’ve built the furniture ourselves, we value it more.

Finding the right balance between stretch and overwhelm is a key leadership judgement. It helps if we have the right people doing the right things, with the skills, experience and conditions to tackle new things, even if they are a challenge. Giving people opportunities to learn and improve with the right support is motivational; setting people up for failure is not.

Purpose

Remember Jordan Peterson’s take on motivation? When we are clear about what an organisation is looking to do, and we share that purpose, we’re more likely to be motivated. Pink believes that when the profit motive “becomes unmoored from the purpose motive”, people are more likely to be demotivated.

Examples of the motivational power of purpose abound. When, in the 1960s, John F Kennedy asked a cleaner at NASA what he was doing, the cleaner replied “I’m helping to put a man on the moon.” Even if this is a myth, it’s a powerful example of purpose in action.

Like others before him, Pink’s Motivation 3.0 model encourages us to take a wider view of what motivates us rather than focussing solely on extrinsic factors. On the ground, if we can identify what drives our people and provide the conditions they need to succeed, we’re well on the way to meeting those needs and motivating them to do and be their best.

We all know when we feel motivated ourselves. We have a positive outlook; we’re excited about what we’re doing; we feel a buzz about doing something that we love, we can do well or that we know is important. We’re enjoying our work, feel that we’re fairly acknowledged, challenging ourselves and learning new things. We’ve reached a state of flow.

Ideally, it’s a feeling we’d like the people who work with us to feel too. As we’ve seen, though, this is much more complicated that just throwing around financial rewards or adopting a one-size-fits-all approach for teams made up of a variety of people with a variety of personalities, preferences and attitudes.

That’s why understanding what motivation is and considering which models and approaches might work best for our own contexts can really help. Armed with this knowledge, we can plan to bring motivation to life, building conditions that create meaning and space for our people to thrive rather than a sense of uphill rock-rolling despair.

Test your understanding

-

Explain the difference between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation.

-

Identify and describe the category of needs at the top of Maslow’s hierarchy.

-

Outline what the acronym ERG stands for in Aldefer’s ERG theory.

-

Explain why Daniel Pink thinks that “carrot and stick” tools for motivation are “so last century”.

What’s does it mean for you?

-

Review and reflect on Daniel Pink’s three Motivation 3.0 factors: autonomy, mastery and purpose. To what extent do these conditions already exist in your team. What else could you do to build a more motivating environment?