If we are to have the impact we want at work – and to protect our own and others’ wellbeing – we need to find the space to ‘be’ as well as to ‘do’.

A few years ago, executive advisory firm Egon Zehnder published the results of a survey into the human side of being a CEO.

Unsurprisingly, doing the top job in this period of rapid transformation is far from easy.

Perhaps more surprisingly, the CEOs surveyed were remarkably candid about the need to keep learning, to transform themselves as well as their organisations, having the open mindsets and self-awareness that would make Carol Dweck and Daniel Goleman very happy indeed.

As one CEO put it: “[It’s about] stepping back and reflecting, acknowledging that I do not have all the answers and do not need to have them.”

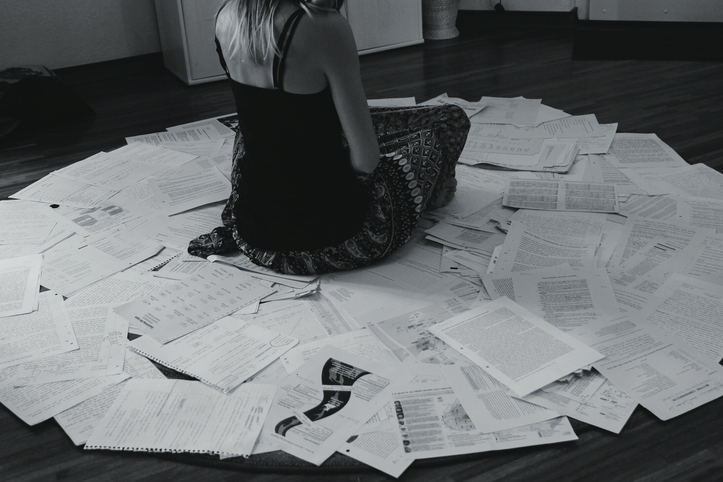

Those top leaders also acknowledged a difficulty many of them seem to face: the tension between what they identify as ‘being’ – working on their personal presence and impact – and ‘doing’, executing the operational requirements of the role.

Aware that the ‘being’ part of their role is crucial to their own – and their organisations’ – wellbeing, many were looking to take proactive steps to protect the time needed to “think and prioritise and maximise my personal impact”.

We ordinary mortals may feel a long way away from an elite pack of global CEOs but it’s intriguing that so many of them could identify with a very real struggle for leaders at all levels: finding the time to be as well as do.

Fostering creativity

Recognition of the link between taking time out and increased creativity is nothing new.

One influential person to observe it was the head of the German Army in the early 20th century, Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord (an undisguised opponent of Adolph Hitler and the Nazi regime).

Rather than promoting officers who worked long into the night, he rewarded those who were able to make the most of their time off. He noted that the periods they spent relaxing and chatting with others not directly connected to their work allowed them to foster more creative strategies than their workaholic peers.

Unfortunately, the great mid-20th century claims that modernity would give people more time – English economist John Maynard Keynes anticipated that 15-hour workweeks would become the norm by 2030 – seem no more than a pipe dream to us these days.

Managing our time effectively, finding the space for that much-needed reflection and perspective, remains a 21st-century conundrum at the very heart of our working lives.

Better, not longer

Yet some respite appears to be coming in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, which accelerated long-term changes in working practices – from an acceptance of remote or hybrid working to a renewed enthusiasm for a four-day working week.

The latter has been shown to enhance both wellbeing and productivity, stimulating a healthy pressure and forced downtime during which workers have the headspace to recharge and focus on other elements of their lives.

In fact, research suggests that a shorter working week:

-

leads to less burnout and fewer absences, making staff happier and more focused.

-

enables more flexible patterns of working and helps firms to attract and retain talented professionals.

-

encourages employees to work more efficiently, prioritising and managing their time better.

-

reduces the commute by at least a fifth, reducing carbon emissions.

-

gives people the chance to connect with their community or to learn new skills; for example, volunteering or undertaking personal development.

Precise models vary, but the four-day working week usually constitutes a 32-hour working week with no loss in productivity, pay or benefits. For example, staff might work Monday to Thursday and have Fridays off, or they may spread these hours over five days.

While challenges remain (it may not suit every industry and needs thoughtful implementation) champions of the four-day week range from Unilever and Microsoft (which trialled it in New Zealand and Japan, respectively) to the nation of Iceland, whose five-year pilot ran from 2015 to 2019. This was proclaimed “an overwhelming success”, improving work-life balance and enhancing the wellbeing of those who took part.

The UK’s trial (which includes Future Talent Learning) was launched in 2022, alongside similar schemes in the US and Australia.

Outcomes over output

Philadelphia-based software company Wildbit transitioned permanently to a four-day week in 2017, putting a laser focus on outcomes over output.

Wildbit’s CEO Natalie Nagele developed a people-first strategy, designed to maximise her teams’ creativity, collaboration and problem-solving, with an emphasis on giving staff the time and space to concentrate. She concluded that a four-day week was a logical part of this.

Her direction was strongly influenced by computer science professor Cal Newport and his emphasis on the importance of facilitating ‘deep work’, which he describes as “professional activity performed in a state of distraction-free concentration that push your cognitive capabilities to their limit”.

In Newport’s book, Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World, he argues that the upper limit for deep work is four hours a day since the brain becomes fatigued after heavy use; we should aim to work better instead of longer, Newport believes.

He sets out four core rules:

-

Work deeply, scheduling time for deep work and creating routines and rituals that make this easier to achieve, without reliance on willpower.

-

Embrace boredom, resting your brain during breaks and allowing it to wander, instead of reverting to inessential tasks. Constantly switching back and forth from focus to distraction, or from distraction to distraction, undermines our ability to concentrate, Newport argues.

-

Quit social media(or at least cut down usage), treating it as a time-stealing diversion.

-

Drain the shallows, removing unnecessary, non-cognitively demanding ‘shallow work’ (such as email correspondence) from your schedule and setting aside blocks of time for shallow and deep work.

Ringfencing pro-time

Other organisations have found ways to build breathing space into the traditional five-day working week.

For example, 3M’s 15% Culture encourages employees to set aside a segment of their time to cultivate and pursue innovative ideas that excite them.

Research conducted by the 4 Day Week Global Foundation points to the benefits of ‘pro-time’. Under this, staff block out distraction-free time to do the ‘important-but-non-urgent tasks’ that sit in the second quadrant of Eisenhower’s Urgent-Important Matrix – the long-term development and strategy activities that we rarely get round to but are vital for individual and organisational success.

But policies such as pro-time only succeed where the time set aside to think or strategise is an integral part of an individual’s workload.

At Google, engineers reportedly referred to its '20-percent time’ policy as “120-percent time”, because it became something that people did in addition to their full workload, rather than replacing a portion of it. There has been speculation about whether the initiative still officially exists.

Busy is the new stupid

Of course, we can’t entirely blame the fast-paced world of work for our time-management challenges.

If we’re honest, some of our innate human characteristics also make us vulnerable to time pressures, distractions and a failure to delegate. For example:

-

we may find it hard to say no because of a desire to please, or a fear of offending someone.

-

we may find delegating difficult because of that perfectionist streak, or an insecurity that we won’t be able to control outcomes effectively enough.

-

we might find it impossible not to check our social media feeds every few minutes.

Some very human traits, such as ego, pride, insecurity or envy can get in the way of even the sincerest desire to use our time efficiently and well; ‘being busy’ can be a status symbol, implying our indispensability.

Busy people were portrayed as ridiculous by the 19th-century Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard. He argued that, far from being important, ‘busy’ people fill their calendars to avoid confronting the general emptiness of their existences — and so distract themselves from the important questions, such as who they are and what their lives are for.

If we want to find more time to be, we need, first, to look to ourselves.

We may not be able to change the world in which we work (at least not all at once), but we can take charge of how we face up to the challenge, tracking our time and how we prioritise it.

In a now-famous exchange, Bill Gates’ amazement at Warren Buffett’s near-empty, analogue diary is an objective time-management lesson for us all.

One of the world’s most successful investors, Buffett also has plenty of wisdom when it comes to making the space to be. Being not without means, he can buy just about anything, but he “can’t buy more time”. So, he has to make the most of the time he has.

The lesson Gates takes from him is that filling up your schedule as a leader is not a “proxy of your seriousness”; there is value, too, in making time to sit and think and read.

It’s up to us all to control our own time. Besides, it’s arguable that leadership is all about thinking – figuring out where our organisation needs to go, how it can get there, and reflecting on the ‘emergent strategy’. This is thinking that develops piecemeal, over time, in the absence of a specific mission and goals.

The power of switching off

Brain science also shows us that busy may really be the new stupid.

An overflowing schedule might well be an indicator that we’re trying too hard to remain in focused-thinking mode for too long.

We often try to concentrate on the issues and problems at hand – the doing – when what we really need is to switch off, to allow our brains to relax and refresh and to make the connections associated with diffuse thinking to facilitate the being.

In an “environment of manic productivity”, we reflect less and limit our growth, echoes leadership consultant Peter Bregman, urging us to take small ‘time outs’ to reflect and recharge.

Writing in Harvard Business Review, he suggests taking a few minutes’ walk in a “metaphorical garden” –the place or situation in which we do our best thinking.

For him, this tends to be a short outdoor activity or a chat with colleagues:

“If I go for a bike ride, a run, or a walk, it’s practically inevitable that I’ll figure something out and come back with a better perspective… This is my favourite, most dependable garden for creative ideas. Another is writing. As I write, my ideas develop and my experiences gently nudge me towards my continuously developing worldview.”

Intentional self-regulation

However, making ourselves take such “restorative action” requires intentional self-regulation, points out British journalist and writer Oliver Burkeman, highlighting what he describes as “the too-tired-to-rest trap”.

For example, we may resort to ‘bedtime procrastination’ when we are so exhausted that getting off the sofa to clean our teeth seems too much of an effort.

He points to research by Christian Jarrett who advises us to start taking non-cognitive breaks early in the day, before we feel we need to, as these bring the most benefit.

“Don’t be shocked if it doesn’t feel good at first,” Burkeman concludes. “When you’re all keyed up on cognitive tasks, stopping can be more painful than continuing. Yes, you need a break. But don’t expect to want one.”

But we also need to accept that, sometimes, simply staring out of that window – not to find out what’s going on outside, but to listen out for our quieter suggestions and perspectives; the unexplored contents of our inner minds – is just the right thing to do.

Cultivating serendipity

It’s not only top businesspeople who understand the power of unleashing our unconscious thought processes; the worlds of art and science are similarly awash with these “eureka!” moments.

While our conscious mind is relaxed, our brain is able to form a creative solution to a problem or finally link ideas that may have been eluding us.

Making those connections is fundamental to another, oft-misunderstood concept: serendipity. Professor Mark de Rond and his colleagues make the case that serendipity is not a proxy for luck or chance.

Rather, its power lies in an “ability to recombine a series of casual observations into something meaningful”.

The good news is that de Rond believes it can be “cultivated, bought and sold” – if we’re alive and open to the opportunities it offers, and prepared to invest time in something that seems to fly in the face of the twin contemporary obsessions of optimisation and efficiency.

But, as a “close relative of creativity”, serendipity offers a degree of “wastefulness” that might benefit us all.

Nor, ironically, can serendipity be left entirely to chance.

We need to put ourselves in the way of those casual observations, whether that’s interrogating the past or spending time with people, especially those who do not necessarily think the way we do.

According to philosopher John Stuart Mill: “It is hardly possible to overrate the value… of placing human beings in contact with persons dissimilar to themselves, and with modes of thought and action unlike those with which they are familiar.”

This, says Mill, is one of the “primary sources of progress”.

It’s an idea at the heart of Herminia Ibarra’s championing of leadership outsight, the need for leaders to seek out fresh, external perspectives and experiences to take us beyond the world of routine operations.

It’s about embracing the new, reassessing how we can add most value in our jobs, developing fresh and different networks and challenging ourselves to experiment and explore.

Beware of the tunnel: the magic of slack

Psychologists Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir pick up on the serendipity-blighting power of day-to-day busyness in their book Scarcity.

They argue that our minds are actually less efficient when we feel we lack something, time included. This scarcity mindset tends to consume all of our mental bandwidth.

Mullainathan and Shafir call it “tunnelling”: focusing so heavily on one thing that everything else goes hang. When we’re talking about time, scarcity – that busyness, our obsession with doing – tends to reinforce our instinct to pack even more into our busy schedules.

Otherwise, we feel that we’re simply not doing enough; that we’re not maximising our efficiency.

In fact, their answer to time poverty is to cut ourselves some slack. We’re generally pretty bad at doing this because we focus on what can be done now and don’t think about what might happen in the future: “The present is imminently clear whereas future contingencies are less pressing and harder to imagine. When the intangible future comes face to face with the palpable present, slack feels like a luxury.”

But without some slack, we’re destined never to catch up with ourselves, always one interruption or unexpected event away from disaster.

Just as some public services found themselves hoisted by the efficiency petard when faced with a global pandemic, so we risk an unsustainable future if we don’t create the slack we need to give ourselves, and our organisations, the perspective we need to see beyond that scarcity tunnel.

Personal wellbeing

That’s all very well, we might say. Yes, we can see that more time and space for working and thinking more deeply, resting and reflecting, building outsight, cultivating serendipity and creating slack is an important part of being a leader.

But what does that mean on the ground?

The range of tips and techniques we can deploy to help us with our time management can get a bad rap. At the extreme, the likes of Oliver Burkeman feel that a focus on time management can simply become another stick to beat ourselves with: “More often than not, techniques designed to enhance one’s personal productivity seem to exacerbate the very anxieties they were meant to allay.”

So how can we make the most of the techniques on offer without taking even more “busy is the new stupid” missteps?

Future Talent Learning’s time management model has four pillars which help leaders to carve out essential time to ‘be’. These comprise the following stages:

1. Planning our time, by recognising where we waste it and putting in place techniques to overcome our personal barriers and keep us on track.

2. Prioritising the tasks that add the most value.

3. Achieving periods of focus while embracing healthy distraction.

4. Managing our timing and energy by matching our schedule to our personal chronobiology.

Undertaking this process is worthwhile because – to counter Burkeman-like arguments – research has shown that the true value of time management is not actually on our personal productivity, important though that is.

Instead, the biggest impact is on our personal wellbeing. Feeling more in control of how we use our time is good for us – and undoubtedly for our teams too.

Filling up our schedules is not a ‘proxy of our seriousness’ as a leader – a role which requires us to ‘be’ as well as to do.

Instead, we should factor breathing space into our working week, allowing our brains to relax, refresh and to make the connections associated with diffuse thinking.

It’s a mindset that embraces pro-time (in which to do important-but-non-urgent tasks), cultivates serendipity (in order to boost creativity) and sets aside time for both deep and shallow work, embracing moments of slack.

As Buffett sums up: “I insist on a lot of time being spent, almost every day, to just sit and think. That is very uncommon in American business. I read and think. So I do more reading and thinking, and make less impulse decisions than most people in business.”

Maybe busy really is the new stupid.

Test your understanding

-

Outline Cal Newport’s four core rules of ‘deep work’.

-

Explain why Bill Gates thinks “busy is the new stupid”.

-

Identify Future Talent’s four pillars of time management.

What does it mean for you?

-

Consider how you might build regular ‘breathing space’ into your own working week. What are your ‘metaphorical gardens’?

-

Reflect on some of the ‘important-but-non-urgent tasks’ you could tackle if you adopted a policy of ‘pro-time’.