When we do something is as important as what we do, and can mean the difference between success and failure.

While Einstein described timing as an art, for author and behavioural science expert Daniel Pink, it is quite clearly a science: instead of making the ‘when’ decisions in our lives using “intuition and guesswork”, we should be following the “systematic, evidence-based clues” that cross-sector research (ranging from economics and social psychology to molecular biology) has unearthed.

His advice applies to a wide range of human experiences and to both big, life-changing decisions and smaller, everyday ones. For example, when it comes to making a fresh start, studies show that we are more likely to follow through when we begin on a ‘temporal landmark’. This could be a ‘social landmark’ (shared by everyone, such as New Year’s Day or a Monday) or a personal landmark (your own birthday or an anniversary).

Meanwhile, people in the last year of a decade (or nine-enders) – those aged 29, 39, 49, 59 and so on – are more motivated to take on big goals for the first time than at any other age; for example, running a marathon, ending a long-term relationship or changing career.

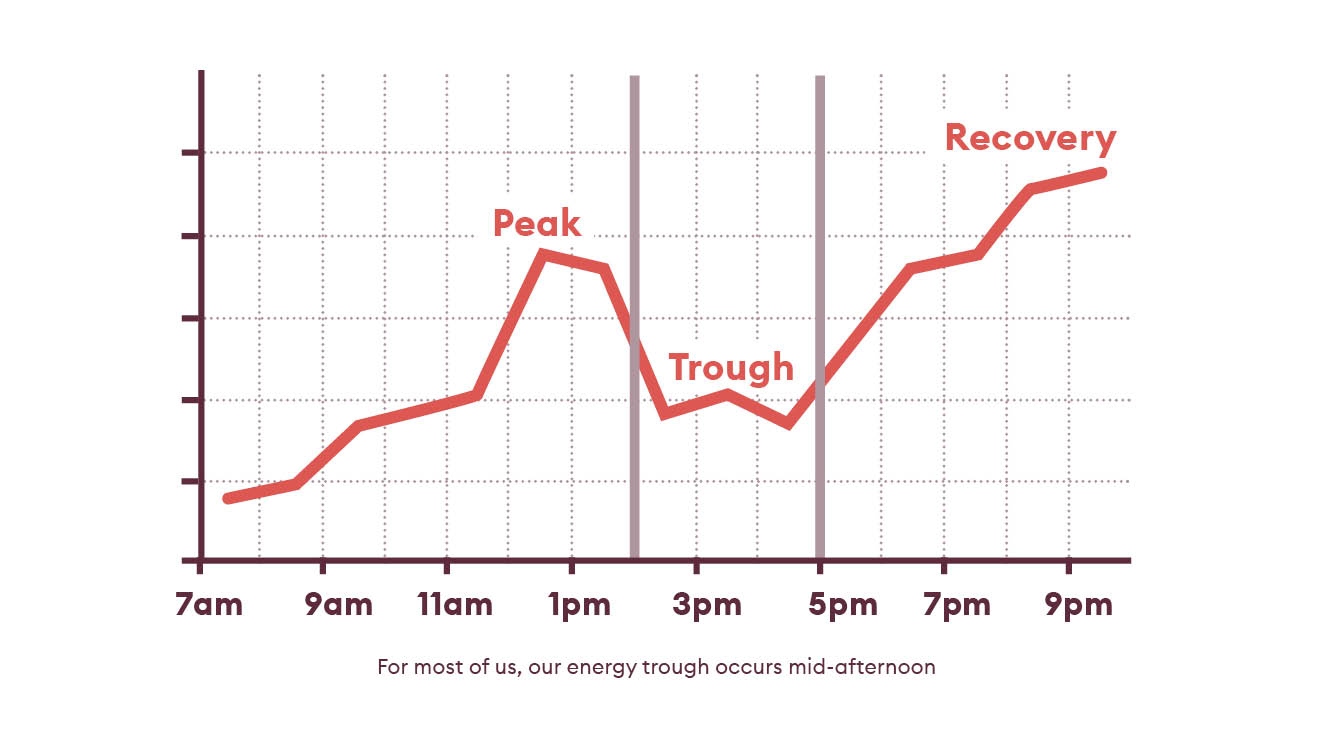

Peak, trough and recovery

And when it comes to day-to-day activities, timing can similarly spell the difference between success and failure – so should be factored into our decision-making at work.

At the heart of Pink’s argument, outlined in his 2018 book When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing, lies chronobiology – the study of our natural daily physiological rhythms. This ‘hidden pattern of the day’ affects our mood, energy, cognitive abilities and, ultimately, our performance, revolving around three stages:

-

Peak: our mood rises – best for deep-focus analytical work, requiring mental alertness.

-

Trough: our mood declines – suitable for simple administrative tasks such as answering emails.

-

Recovery: our mood picks up – ideal for work that involves mental ‘looseness’, such as insight and creativity – considering ‘the bigger picture’.

The exact timing of each person’s peak/trough/recovery varies according to their specific chronotype (or personal circadian typology), which defines their productivity times.

Pink broadly divides people into ‘larks’ (morning people – who peak in the morning), ‘owls’ (evening people – peaking in the evening) and ‘third birds’ (somewhere in between).

Approximately two-thirds of us fall into the ‘third bird’ category, while around 20% are owls and 15% larks. The modern working day is more suited to larks and third birds than it is to the fifth of the population who are owls.

Our chronology is not set in stone, Pink adds. For example, it tends to evolve with age: children tend to be larks, waking their parents at the crack of dawn; teenagers and young adults usually then morph into owls who struggle to get out of bed in the morning, while older people tend to return to lark characteristics.

To work out your own chronology type, simply ask yourself:

-

what time do you usually go to bed when you’re on holiday – or when you have nothing much to do the next day?

-

what time do you usually wake up on those days?

-

what is the midpoint between those two times?

For example, if you normally go to bed at 2am and wake up at 10am, your midpoint is 6am.

-

If your midpoint of sleep is 3.30am or earlier, you’re a lark.

-

If your midpoint of sleep is 5.30am or later, you’re an owl.

-

If your midpoint is somewhere in between, you’re a third bird.

How does this impact on work?

Since most people peak in the morning, are least cognitively alert after lunch and rebound in the evening, managers need to take this pattern into account, becoming intentional and strategic about scheduling different activities.

Rather than putting meetings in the diary according to availability or convenience, Pink argues that we should be thinking about what kind of meeting it is. For example, is it an analytical, administrative or creative meeting and (if we want to go a step further) are the people joining it morning people or evening people?

Studies underline the importance of this. For example, researchers studied transcripts of 26,000 earnings calls made by 2,100 companies over six and a half years to measure the emotional content of these calls and plot them against time of day. They found that afternoon calls were more negative, irritable and combative, leading to temporary stock mis-pricings for firms hosting earnings calls later in the day.

“An important takeaway from our study for corporate executives is that communications with investors, and probably other critical managerial decisions and negotiations, should be conducted earlier in the day,” concluded Pink.

Restorative breaks

When activities cannot be scheduled for optimum times, ‘restorative breaks’ can provide benefits, helping us to re-energise and re-focus. In fact, breaks are a part of work, according to Pink.

To illustrate this, he explains that, for children, taking a test after a 20- to 30-minute break produces scores that are equivalent to spending three additional weeks at school per year and having wealthier and better-educated parents; taking the same test in the afternoon without a break produces scores that are equivalent to spending less time in school per year and having parents with lower incomes and less education.

If this isn’t compelling enough, in a study of parole hearings, it was found that judges were most likely to grant parole at the beginning of the day and after breaks, with their leniency declining as the day went on.

To take a break effectively, Pink suggests the following:

-

Get up from your desk. Go outside, if possible.

-

Be social. Break together.

-

Don’t do work on your break, and try not to use your phone.

-

Schedule your breaks into your day.

And for those of us working from home (an accelerating trend), he prescribes combining a coffee and a nap, aka a ‘nappuccino’, ideally after lunch. Nice work if you can get it.

Test your understanding

-

Outline how and why timing should be factored into our decision-making at work, according to Daniel Pink.

-

Explain what an effective restorative break might involve.

What does it mean for you?

-

Identify your own chronology type and consider how you might make changes to your schedule to take account of your own peak and trough times.