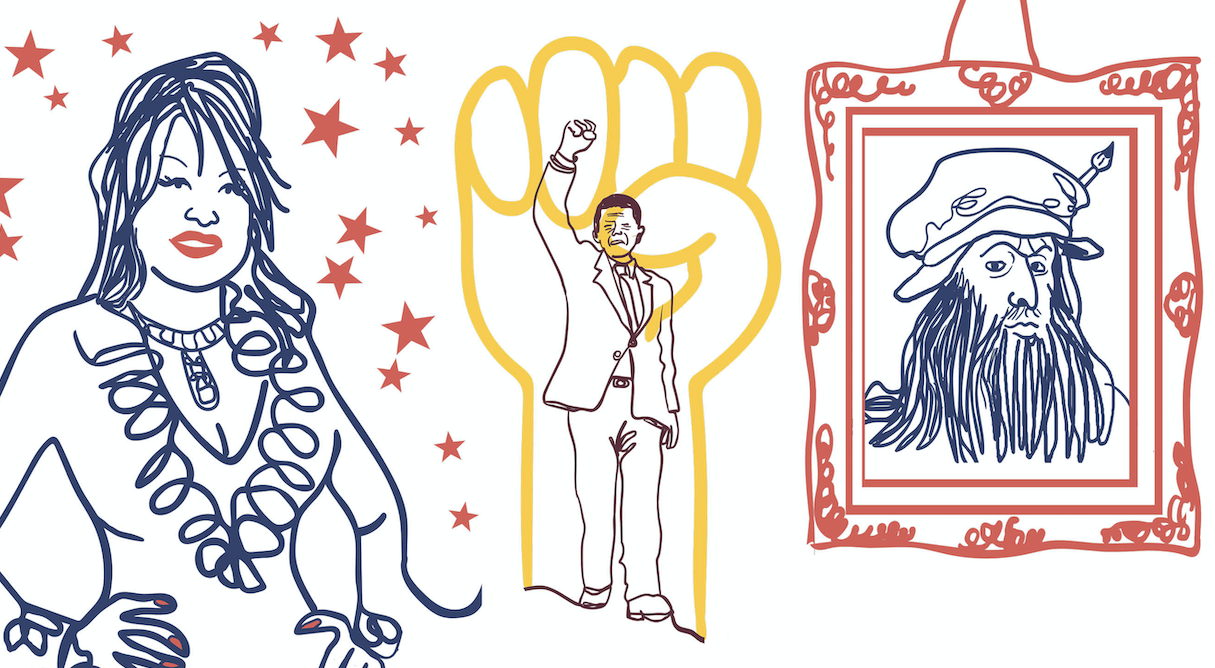

You’ll notice in our Nutshells that we often refer to cultural icons who have been living embodiments of some of the ideas we’re discussing. Below we list exemplars of foundational ideas from our content about self-management: Dolly Parton, Leonardo da Vinci and Nelson Mandela.

Career agility: Dolly Parton

(Workin’) 9-to-5 may feel less than pertinent in our brave new world of flexibility, but Dolly Parton – The Queen of Country (and much more besides) – remains as relevant as ever.

Deliberately nimble in her career, Parton keeps in step with the times (or runs ahead of them), managing, simultaneously, to be an iconic singer-songwriter (straddling pop and country music), an award-winning actress, a $500m business powerhouse, pioneering feminist, humanitarian, and part-owner of a theme park celebrating Appalachian culture (Dollywood).

Steadfast in her identity, she is unapologetically herself, staying firm to her faith and family values, and studiously ignoring the critics who warned her she wouldn’t be taken seriously due to the way that she dresses.

It’s a combination of stability and versatility that has won her fans from across generations and racial, political, gender and class divisions – rendering her a unifying figure in a divided world.

Parton credits her personal enterprise, adaptability and resilience to growing up “dirt poor” alongside 11 siblings in a one-room cabin in Tennessee. Honing her musical gift in front of an audience of chickens in her family’s yard (reimagined as adoring fans), she used these qualities to propel herself from local radio to the bright lights of Nashville. Later, this same agility gave her the courage to part ways with her mentor, Porter Wagoner, to seek a solo career.

Hard graft (and regularly rising at 3am) has always been part of her success, but it’s Parton’s willingness to adapt to changing circumstances that makes her a Future Talent Learning Transformational Hero embodying career agility. At a time of high-speed social, economic and technological change, none of us can rely on traditional career patterns or static skills. Today, we must be prepared to think fast, change course regularly, keep learning and thrive in a dynamic marketplace, embracing a wide range of perspectives.

From early in her life, Parton was quick to seize (or create) opportunities, try new things (“you never do a whole lot unless you’re brave enough to try”) and collaborate widely. She’s also able to survive setbacks, fortifying her in-built resilience and self-awareness with a quick wit and self-deprecating humour; she’s known for combating insults by beating people to the punchline (“It takes a lot of money to look this cheap”).

In 1994, Parton published her first autobiography – Dolly: My Life and Other Unfinished Business – clearly signalling that, despite fame and fortune, she had plenty more to experience and much to achieve. Two decades and another memoir on, she refuses to retire (during COVID-19, the 74-year-old invested $1m in the groundbreaking Moderna vaccine and in creating a parody of Jolene to combat vaccine hesitancy; a year later, she was penning her first novel with crime writer James Patterson).

Rather, she is trailblazing the multi-stage life as agilely as she has pioneered so many other things during her career.

“I’d rather wear out than rust out,” says Parton. “You only have one life.”

Curiosity: Leonardo da Vinci

The early 1450s were a particularly propitious time to be born if you were of an innovative and experimental nature. Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press. The scholars of Constantinople, fleeing the Ottoman Turk invaders, were flocking into Italy, bringing with them the wisdom of the ancients. And, in a small hilltop village 20 miles from Florence, Leonardo Da Vinci made his first appearance on earth.

Described by British art historian Kenneth Clark as “undoubtedly the most curious man who ever lived”, Leonardo da Vinci brought new meaning to the idea of being a polymath, even within a period known for its broad-ranging humanist ideals.

He excelled as an artist – producing renowned paintings such as the Mona Lisa and the Last Supper – but also as a scientist, architect and engineer.

Spurred by a seemingly limitless thirst for knowledge, and a desire to understand the universe and how humans fit into it, da Vinci explored every possible field and discipline from mathematics, anatomy and astronomy to botany, geology and music. His Vitruvian Man, a study of the proportions of the human body, provides a visual metaphor for this, linking art and science in a single work.

Meanwhile, as an inventor with an imagination way ahead of his time, he came up with the concepts and structural designs for many innovations that have since become realities, including an early version of the parachute, diving gear, cranes, gear boxes and a range of flying machines.

Relentless curiosity simply flowed through da Vinci’s veins, and being largely self-taught, he prioritised experience, observation and experimentation over formal learning or received knowledge. He wanted to know everything about everything, and would traverse the countryside in search of answers to things he didn’t understand (“why is the sky blue?”) or sketching flowers and plants from multiple angles, to understand their anatomy. In his notebooks, he would also jot down people’s expressions and emotions, trying to relate these to the inner feelings they were experiencing. “Learning never exhausts the mind,” he argued.

In this way, he cultivated a T-shaped mindset, developing both expertise in certain areas and a broad base of supporting knowledge and skills, which gave him an ‘inner diversity’.

This same inquisitive and questioning nature carried through into his personal life, in which da Vinci was known to be quirky, with a penchant for wearing linen and dressing in pink. “He was illegitimate, gay, left-handed, vegetarian, somewhat of a heretic, a rebel. He was a real misfit,” wrote his biographer Walter Isaacson, who believes this freed him to explore. Ultimately, he was fuelled by an almost childlike sense of wonder in everything that he experienced.

As adults, we often stop being curious, focused less on gathering knowledge than on our emotional and relationship goals, and are unwilling to challenge the assumptions we have developed over the years. To overcome this, we must keep on learning, cross-pollinating our existing knowledge and skills with insights from other disciplines and perspectives.

Like da Vinci – the ultimate Renaissance Man and Transformational Hero for curiosity – we can become intentionally curious, broadening our networks and interests, challenging our confirmation biases and listening without judgement. All of this can then be funnelled into the creativity and innovation that are so vital in the 21st-century workplace – where each of us needs to be both specialist and generalist, cultivating the depth and breadth that underpins a T-shaped mindset.

Resilience: Nelson Mandela

“Do not judge me by my successes, judge me by how many times I fell down and got back up again,” said the man revered for his part in toppling South Africa’s racist system of apartheid. Nelson Mandela, a political prisoner destined to become the first black president of his country, was a man of principle, a visionary fully “prepared to die” for democracy – and a true disciple of stoic resilience.

During his 27 years of incarceration, including 18 in a tiny cell on the notoriously harsh Robben Island, ‘Prisoner 46664’ endured a regime of physical abuse, hard labour and solitary confinement. He faced it with a mindset of deliberate optimism and calm fortitude, recognising that mental strength and emotional regulation lie at the heart of survival. “I learned that courage was not the absence of fear but the triumph over it,” he explained.

Preserving his mind with daily meditation and his body with the strenuous workouts that gave him an outlet for tension, Mandela refused to give in to despair. Instead, he drew sustenance from his purpose and the knowledge that he was “part of a greater humanity than our jailers could claim”, driving an in-prison movement of civil disobedience that pushed officials to improve conditions for all inmates.

He took back his dignity and a sense of control by realising that, while he couldn’t instantly change his immediate circumstances, he could manage how he responded to them, noting, for example, that it was essential to his mental wellbeing that he treated his jailers with empathy rather than animosity. Ultimately, he gained their respect and that of his fellow prisoners with his humility, compassion and dry sense of humour. He refused all conditional offers of release.

Even when he was finally liberated in 1990, Mandela refused to indulge his negative emotions: “As I walked out the door toward the gate that would lead to my freedom, I knew if I didn’t leave my bitterness and hatred behind, I’d still be in prison,” he wrote in his autobiography.

Representing our Future Talent Learning Transformational Hero for resilience, Mandela clearly demonstrates an innate fortitude, while also showing that resilience can be enhanced, even as we face situations that push us to our limits. He described prison as “a tremendous education in the need for patience and perseverance”.

While few of us will require the level of resilience he did, nor for such a length of time, it’s inevitable that we will all face setbacks and pressures in our own lives and careers that threaten to overwhelm us. Resilience is also predicted to be a critical characteristic for workers to develop in the ‘never-ending storm’ of job changes and disruption caused by artificial intelligence and new technologies.

To cope, we must tap into our mental strength, and adopt attitudes and strategies that give us the psychological toughness to handle adversity and to bounce back again – and again.

This involves practising resilience proactively and intentionally, so that when demands are placed upon us and difficulties arise, we are equipped to overcome them with our physical and emotional health intact.